The market decline experienced thus far is closer to its beginning rather than its end. Today’s refreshing market rise is likely just a flash in the pan.

There is nothing that politicians or regulators can do to prevent the natural price discovery that is critical to the long-term health of our capitalist system.

The market needs to go down again before it can sustain any future rise.

We simply must deal with the loads of toxic and mis-allocated capital that our profligate society has created over the past 20+ years.

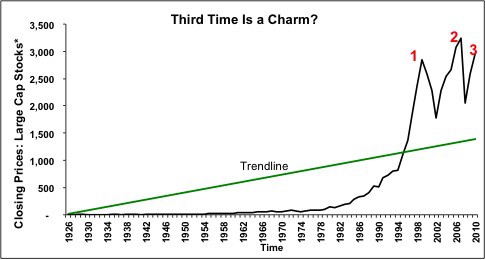

Allow me to explain how we got ourselves in this situation. Figure 1 highlights the three successive stock market bubbles in just over 10 years. Compare the size of these bubbles and the rise in stock prices over the last 25 years compared to the prior 65 years. A simple trendline further accentuates just how much stock prices have appreciated compared to historical trends.

Figure 1: Historically Enormous Stock Market Bubbles Keep Coming Back

I am not suggesting that stock prices should revert to the long-term trendline. I fully appreciate the accelerating pace of innovation realized by our society and its impact on standards of living and improved utilization of resources.

There is no question that we live in unprecedented times of prosperity and wealth creation. And technology holds great promise for the future achievement of mankind and will drive improvement in the standards of living around the world.

The problem is that we have gotten ahead of ourselves. By how much, I am not sure. But I am sure that we are due a (lasting) correction in the stock market, and the longer that correction is put off, the more painful it will be.

To illustrate, let’s review what drove the first two market bubbles.

- Tech bubble – irrational exuberance about the value in tech stocks combined with rather loose monetary policy pushed stocks and capital flows to ridiculously high levels

- Housing bubble – lax lending standards, unscrupulous bankers, conflicted regulators, a bottomless appetite for consumer spending and a seemingly infinite amount of cheap money to finance consumption.

Now, let’s review what happened after these bubbles burst.

- After the tech bubble: monetary policy remained highly accommodative and government stimulus was aplenty

- After the housing bubble: monetary policy remained highly accommodative and government stimulus was aplenty

See the response pattern? See how it affected the markets?

It is as if the bubbles never burst. Game back on. Like a high-school party, the music stops and everyone is quiet when the cops show up. Someone convinces the cops that nothing unscrupulous is going on and all will be calm and quiet. Then, as soon as the cop car is out of sight, the music gets turned back on and the party goes harder.

What will be the response to the third bubble that has formed?

That is the question that I think the market is finally facing. The answer is not the same as before.

The government has run out of stimulus and policy bullets.

Really, what else can politicians and regulators do to engineer a soft landing, or should I say, another bubble.

Figure 1 shows that we never really landed. We rocketed from one bubble to the next.

Let’s take a look at the options available via the two main forces for stimulating economic recovery:

- Fiscal policy – given the federal, state and municipal debt and budget problems, another round of stimulus spending or another TARP-like program is probably not in the cards. The funds are simply not available. Not to mention, I do not think another bailout plan would go over very well with tax-payers.

- Monetary policy – here we have three potential options.

- Lower rates – can they go any lower? The answer is not meaningfully lower unless the Federal Reserve wants negative nominal rates. In addition, low interest rates undermine long-term economic growth potential.

- Extend QE2 to QE3 – given that the point of QE2 was to keep interest rates, especially mortgage rates low, I do not think additional quantitative easing in the form taken so far would have much if any impact on rates given how lower they already are. Moreover, driving oil and other commodity prices higher by further undermining the value of the dollar is not exactly conducive to growth.

- A new type of QE3 – suppose the Fed were to purchase large amounts of assets other than treasuries such as foreclosed homes. I think that action would likely spook investors because it would signal that the carrying value of those homes were too high. Otherwise, private investors would have already bought them for their own portfolios. And bank stocks would sink as investors realize that additional write-offs might be coming. The same reaction applies to any other asset that the Fed might choose to take off private investors’ hands.

So, who is going to bail us out this time?

My overriding message is that no one should have bailed us out to begin with. The longer we avoid the painful process of deleveraging and returning to a more deliberate and rational mode of capital allocation, the more we delay the inevitable. The more we shift the blame for our financial mistakes to the public sector, the deeper the hole we must dig out of.

Which brings me to the next point: shifting responsibility to the public sector, i.e. government, presents some very serious problems and headwinds for future growth:

- The government is not bailing anyone out, taxpayers are. In essence, the government is using hard-earned tax revenue to pay for the mistakes of certain members of our society.

- Moral hazard is confused with moral obligation. Re-distribution of wealth to those that are in genuine need of assistance from society is in our long-term best interests. But moral obligation quickly becomes moral hazard when the re-distribution applies to people who should, but prefer not to, care for themselves.

- When the people who make mistakes do not pay for mistakes, they keep making them…bigger and bigger. Can you say “mortgage back securities”?

- We run out of money. When capital from productive sources is siphoned away to subsidize unproductive investments, capital is destroyed and never to be found again. When there is less capital available for productive investments, growth is forced to slow as are incomes and payrolls.

- When growth slows and jobs are not available, bad things happen. For an example of bad things happening now, take a look at the riots in the streets in London.

Until we allow the natural price discovery that unfettered markets are designed to provide, we continue to subsidize unproductive investments. And the longer we subsidize unproductive investments, the more wealth (and jobs) we destroy in the present and in the future.

Sure, it feels better when the stock market skyrockets, bank accounts are fat, growth is strong and the financial future is bright. Wasn’t that what we got in the 1990s, then again in the first decade of this century?

It cannot go on forever. Consider how much the housing bubble was driven by too much borrowing? Though financing might be cheap and easy to get for extended periods of time, there is not an infinite supply.

At its core, borrowing is simply a method of cashing in today on future earnings. The more we borrow against future earnings, the less we have in the future.

Using borrowed funds to subsidize unproductive investments only compounds and accelerates wealth destruction.

Keynesian policies can be successful in certain situations and for limited amounts of time, but they cannot be sustained infinitely. Borrowing and spending by the government can help the economy survive a soft patch or decrease the depth of a recession, but it does not fix the underlying capital allocation problem.

Keynesian economic policies are patches to economic problems, not fixes. If extended for too long, they only make matters worse.

Before the housing bubble, the government was levered to the hilt. After the housing bubble, consumers are also levered to the hilt. Both are struggling to balance their checkbooks.

So who is left to bail us out? Only two potential candidates: American corporations and foreign countries.

A quick survey of the status of the other major economic powers is not exactly inspiring. China is slowing growth to fight its inflation problems. The European Unions, well, they have their own problems. Japan is not exactly prospering. In general, there are few, if any, global economic bright spots. None are large enough to bail out anyone.

There are many bright spots in corporate America. Companies like Apple (AAPL-very attractive rating), Google (GOOG-very attractive rating), Microsoft (MSFT-very attractive rating) and many others are as profitable as ever. Their returns on capital rank among the very best in the world. They are shining examples of capital realizing its highest and best use. For the country as a whole, cash flow returns on assets are near all-time highs. Much of the recent profits, however, have come at the expense of the consumer as wages have grown much more slowly than profits.

Then, there are the banks. US banks recently enjoyed the largest bailout in the history of the world. Further, their profit margins have been subsidized by sustained low interest rates. And yet, they are lending little money.

Is the problem that banks do not want to lend or that there are not enough borrowers?

I think the answer is both. Many banks are still carrying a great deal of toxic assets. With so much risk already on their balance sheet, they cannot afford to take on more.

As for borrowers, the uncertain tax, regulatory and economic outlooks are not exactly enticing entrepreneurs, small and large businesses to take risk.

To summarize, there is no one left to bail us out this time.

So, what happens next? We buckle down and face the long hard road to true, not artificially subsidized recovery.

We recognize facts:

- We cannot spend more than what we make forever. Seems like an obvious statement, but that is not how the United States has operated over the past several years.

- We have wasted lots of capital by subsidizing unproductive investments.

- We have delayed the process of creative destruction whereby unproductive investments are replaced by productive investments.

- Because of our wastefulness and the delay in creative destruction, much time is required to restore wealth back to the levels to which we have become accustomed.

- We must rebuild diligently, rationally and deliberately to ensure capital realizes its highest and best use.

- Kicking the can down the road, Euro-style, only delays the inevitable and makes the problem worse.

- Eventually, we will be much better off than what we started.

In the meantime, the stock market and economic activity will continue to suffer. No pain no gain.

Disclosure: I am long GOOG, AAPL and MSFT. I receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector or theme.