The city of Nashville was founded in 1779 and grew quickly due to its location as a river port, central position in the U.S., and, eventually became a main railroad center. Fast forward nearly 250 years, and Nashville was a top landing spot for the droves of people moving amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

We’ve all heard the stories.

The Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce estimated 98 people moved to Nashville per day in 2022. This is up from an already high ~85 people per day in the mid-2010s. With the aspiring singers, priced-out Californians, and overworked New Yorkers came an issue that made Nashville a victim of its own success: traffic.

According to the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, the average cost of congestion in Nashville is $1,465 per commuter annually. Between I-24, I-40, I-65 and I-440, Nashville is home to four of the top 100 bottlenecks in the U.S, and it’s been ranked the 131st most congested city in the world. The future outlook is grim: according to the Tennessee Department of Transportation, commute times could increase 60% in the next 20 years if nothing is done about the current situation.

Apart from traffic, the population influx drove Nashville’s average home price from $155,000 in 2009 to $432,000 in 2023, which triggered an affordability crisis as average rents increased 50% in the past decade.

The story of Nashville is at the intersection of two defining aspects of the last decade: frothy markets and neglected infrastructure.

Let’s dive in.

Failing Grade

The infrastructure of the United States, a critical foundation for the nation’s economy and social welfare, is in a state of alarming disrepair. Over the last five decades, public investment in U.S. infrastructure has declined by more than 40%, which results in aging and overstretched systems. Once considered a global leader, the U.S. now ranks 13th in overall infrastructure quality according to the World Economic Forum.

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) recently gave the nation’s infrastructure a grade of C-, which is actually an improvement from a D+ in 2017. While incremental enhancements have occurred in certain areas like railroads and drinking water systems, the overarching picture remains grim. Nearly half of the country’s bridges are over 50 years old, and more than 43,000 are rated as structurally deficient. Moreover, 45% of Americans lack access to reliable transit, with existing systems aging and in desperate need of repair.

On the roads, over 1 in 5 miles is in poor condition, contributing to substantial societal costs. Congestion and unsafe roadways cost almost $160 billion annually and lead to over 30,000 traffic-related fatalities each year. Furthermore, a lack of investment in electric vehicle charging stations and the continued reliance on diesel fuel in buses, primarily school buses, pose significant health risks and environmental challenges.

Water infrastructure represents another concerning area, given that millions still rely on lead pipes despite the irreversible health damage from lead exposure. The calamity in Flint, Michigan, serves as a grim reminder of the potential consequences. Drinking water, wastewater, and irrigation systems alone will require $632 billion in additional investment over the next decade.

Energy systems are also under stress. Ports and waterways handling over one-fourth of the country’s freight transport face escalating delays. The electrical grid’s operators struggle to invest adequately, which leads to increasing power outages, billions of dollars in unnecessary costs, mass destruction, and, even, deaths.

California’s PG&E, for example, neglected its electrical equipment for so long that it’s estimated to be responsible for 31 wildfires, 113 deaths, and the destruction of nearly 1.5 million acres. Not only does PG&E’s neglect of important infrastructure lead to its demise and bankruptcy in 2019, but taxpayers are also forced to pay for the damages out of their wildfire fund. Talk about lose-lose at horrific scale.

To avoid further disasters, the state of California alone will need to spend $50 billion by 2035 to update its electrical grid so that it’s suitable to handle the state’s rather lofty electrical vehicle adoption mandates.

Broadband access, a lifeline in modern society, has also been neglected. An estimated 18 million Americans, primarily in rural areas, lack access to reliable, fast internet, thereby widening the “broadband gap” and stunting economic growth in underserved communities.

If left neglected, the nearly $2.6 trillion “infrastructure investment gap” could cost the U.S. $10 trillion in lost GDP by 2039 and lead to more than 3 million job losses. Crumbling infrastructure costs every American household an average of $3,300 annually in hidden expenses from lost time in traffic to extra car repairs.

The state of infrastructure in the U.S. goes hand in hand with the past decade of malinvestment in capital markets, which wiped $9 trillion in wealth from Americans from January to September 2022. This decline in wealth highlights the pitfalls of poor capital allocation – more on that below.

Hollow Markets

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.” (Milton Friedman)

In the thick of the Great Financial Crisis, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke cut interest rates from 2.0% to effectively 0% from August to December of 2008. What was meant to be an emergency measure to calm investors and signal the government’s commitment to stabilize markets and the economy became surprisingly convenient…and long-lasting.

The economy slowly started showing signs of life, and markets began to recover. What followed was the longest period of near-zero interest rates in history, which upended investing and economic activity as we’ve known it, and, in our opinion, not always in a positive way.

Something interesting happened at the topsy-turvy region of the zero bound: at very low interest rates, a marginal cut in interest rates failed to spur the increase in risk-taking and productive economic activity that economists would expect. Instead, market actors felt compelled to borrow in order to engage in speculative, rent-seeking, and often, fraudulent behaviors.

Here’s a good example: the offsetting of share buybacks by large corporations which were awash in cheap (read: free) capital from 2009 to 2021.

Here’s how it worked:

- Corporations either used their cash, or worse, borrowed (at low rates) capital in order to buy back their own shares

- The same corporations issued large amounts of new shares to senior and mid-level management and effectively reversed the reduction in share count that was supposed to benefit shareholders

- Through non-GAAP financial gymnastics, the corporations patted themselves on the back and publicly claimed a serious commitment to returning shareholder capital.

Take Meta Platforms (META), formerly Facebook, for example.

From 1Q12 through 3Q22, the company deployed nearly $96 billion of (shareholder) capital to buy back shares. However, a deeper look paints a different picture.

While the company bought back 378 million shares via buybacks, it issued 431 million new shares to employees and actually increased its shares outstanding by 12% during that period.

Meanwhile, here’s what we saw in the media:

Figure 1: Meta Buyback Coverage

Source: CNBC, The Motley Fool, BNN Bloomberg

All this maneuvering created no value.

It produced nothing. It employed no one. It didn’t lead to a patent, it didn’t spur capital investments, or have knock-on effects. It was a mere transfer of wealth through financial trickery and hazy narrative – in this case, from shareholders to Big Tech corporate managers.

At the same time, the 2010s were a time of moral decline. An air of nihilism pervaded the investment profession: if teenagers in a basement were outperforming seasoned investment managers by buying the latest crypto coin or meme stock, what was the point of diligent investment research? Bored apes don’t care about fundamentals!

The zeitgeist of the era gave us meme stocks, the GameStop saga, and the rise and fall of the ebullient cryptocurrency market. Once again, each event largely a transfer of wealth without a balancing creation of value in the real economy or service to society.

Bubble behavior became the water we swam in, in both public and private markets. Much like other periods of financial mania, fraud was rampant. This was the golden age of the scam, the years that gave us Adam Neumann (of WeWork infamy), Martin Shkreli, Anna Delvey and Elizabeth Holmes. It seemed that market actors, sophisticated or not, just wanted to make a quick buck.

Figure 2: The 2010s Malinvestment Starter Pack

Source: New Constructs, LLC

As the Fed was slowly raising rates in order to get ahead of long-awaited inflation, the COVID-19 pandemic came and changed everything. Not only did the Fed reverse course, but it nearly doubled its balance sheet from $4 to $7 trillion in the span of 4 months, a money-printing experiment of unprecedented scale.

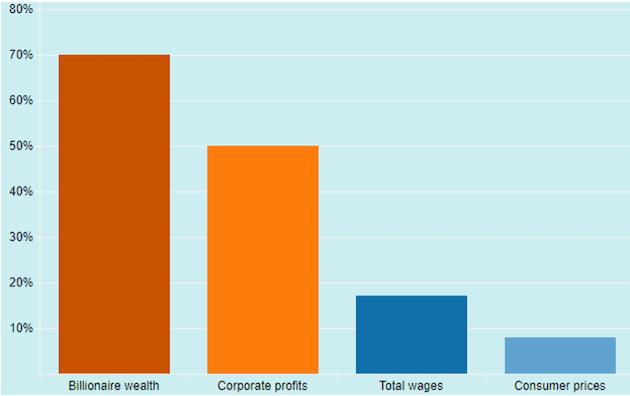

Though the emergency measure (sound familiar?) did put money in the hands of those who needed it, it exacerbated issues that were present before the pandemic. Wealth inequality worsened significantly, with billionaire wealth skyrocketing while workers struggled to make ends meet with modest wage gains to pay for higher prices at the gas pump and supermarkets.

Figure 3: Percentage Change During The COVID-19 Pandemic

Sources: Inequality.org

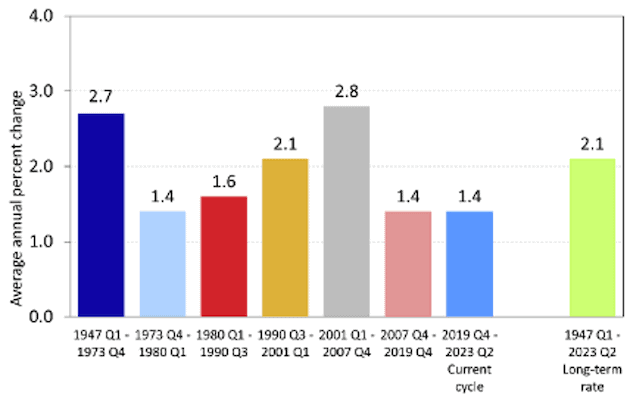

Rising wealth inequality, coupled with the perverse effects of social media, fueled widening political polarization, culminating in movements such as Antifa and QAnon. And what’s worse, after it was all said and done, the period of greatest manufactured wealth in recorded history ended up being one of timid societal advancement and no productivity growth. Productivity growth since 2007 equals levels last seen in the 1970s and is well below its historical average. See Figure 4.

Figure 4: Productivity Growth In The Nonfarm Business Sector: 1947 – 2023

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

In other words, in the years after the financial crisis:

- Vast sums of wealth were artificially created

- This wealth did not lead to significant improvements in productivity or innovation

- This wealth did not significantly raise the purchasing power of the average citizen

- This wealth was transferred, in several ways, to noise traders, speculators, and Wall Street insiders willing to participate in a warped zeitgeist.

This time period can all be summarized with one word: malinvestment.

Think about the previous section, where we outlined the declining state of U.S. infrastructure. The country had a choice to improve its infrastructure significantly (and boost productivity gains for decades to come), but instead, we chose meme coins and vaporware. The rich got much richer, while the rest of society suffered.

Not all is lost, though. The U.S. Government recently passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021, which earmarks $1.2 trillion for investments in U.S. infrastructure and clean energy initiatives. Though the act was passed at great political cost, it represents nearly a quarter of the money-printing from February to June of 2020.

Additionally, signs of rational thought and better investment decision-making (see the lack of speculative IPOs since the boom of 2021) have returned to U.S. markets, albeit at a slower rate than we’d like to see. A return to quality capital allocation, in equity and debt markets, can coincide with a new era of infrastructure investment and improve the lives of all citizens.

Fiscal Trifecta: A New Dawn

Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA)

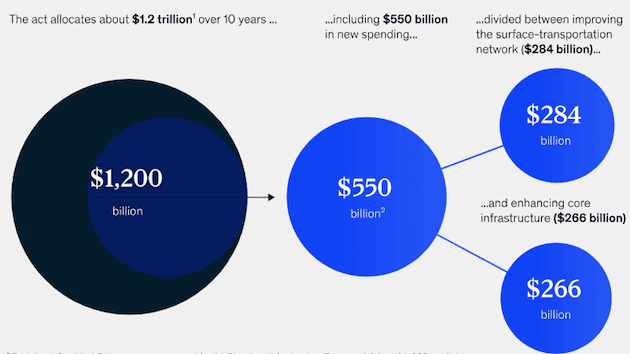

The Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act’s (IIJA) objective is to revitalize the United States’ infrastructure, addressing pressing needs in transportation, broadband, and public works. The IIJA further aims to extensively upgrade the aging roads, bridges, and essential utilities by allocating an estimated $1.2 trillion over ten years.

Of this amount, $550 billion is marked for new spending in the upcoming five years divided between surface-transportation improvements ($284 billion) and core infrastructure enhancements ($266 billion). The transportation funding includes allocations for roads, bridges, rail, airports, ports, public transit, electric vehicles, and safety measures. Core infrastructure spending focuses on the power grid, broadband expansion, water management, environmental resiliency, and pollution remediation, with a targeted emphasis on inclusivity and sustainability.

Furthermore, $300 billion in formula grants, including allocations to the Highway Trust Fund, will be disbursed to states, primarily benefiting Texas and California. These grants are designed to be distributed based on specific factors like population size, with most of the funding earmarked for roads and bridges.

Figure 5: Breakdown of IIJA Funding

Sources: McKinsey

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA), constitutes a comprehensive approach to stimulate clean energy, reduce healthcare costs, and enhance tax revenue collection.

A major part of the IRA is aimed at climate efforts, with nearly $400 billion directed towards clean energy. Clean electricity and transmission are prioritized, alongside clean transportation, including electric vehicle (EV) incentives. With regards to energy infrastructure, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office will receive roughly $12 billion to expand its existing loan authority and establish a new $250 billion loan program for upgrading, repurposing, or replacing energy infrastructure.

In addition to public spending, the IRA offers incentives for private investment. The largest portion of the $394 billion in energy and climate funding takes the form of tax credits, mostly directed at corporations, and amounts to an estimated $216 billion. These tax credits are aimed at spurring private investment in clean energy, transport, and manufacturing.

Consumer incentives are also significant in the IRA, with $43 billion in tax credits intended to make EVs, energy-efficient appliances, rooftop solar panels, and other green technologies more affordable. Specific tax credits are available for new and used vehicles, home improvements, and heat pumps starting in 2023.

On the revenue side, the IRA introduces measures to offset new spending, including raising the minimum tax on large corporations to 15%, imposing a 1% excise tax on stock buybacks, and augmenting IRS collection and enforcement. Along with savings from healthcare initiatives, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the IRA will decrease government deficits by $237 billion over the next decade.

Overall, the IRA represents a significant step in aligning federal spending with contemporary economic, environmental, and societal goals, with implications for various sectors, investors, and the broader U.S. economy.

CHIPS Act

The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS Act), signed into law on August 9, 2022, aims to reinvigorate domestic semiconductor capacity, drive innovation in critical technology fields, and foster a more inclusive STEM workforce. With an investment of $280 billion over the next ten years, the act’s provisions are multifaceted.

The bulk of the funding—$200 billion—is designated for scientific R&D and commercialization, particularly in emerging technologies such as quantum computing, AI, clean energy, and nanotechnology. In the realm of semiconductors, the act allocates $52.7 billion to manufacturing, R&D, and workforce development, and is supplemented by $24 billion in tax credits for chip production and $3 billion for leading-edge technology and wireless supply chain programs.

This investment comes in response to the reduced domestic share of global semiconductor manufacturing, which has fallen from 37% in the 1990s to just 12% in 2022. The fragility of overseas chip supply chains has been exposed in recent times, which underlines the necessity for domestic manufacturing expansion.

To encourage private sector participation, the CHIPS Act includes a 25% advanced manufacturing investment tax credit for investments in semiconductor manufacturing equipment, which is projected to cost $24 billion over five years.

Build Back Better

The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the IIJA, and the CHIPS Act will give the country a much-needed chance to revamp its infrastructure, invest intelligently in the energy transition, and ensure that the U.S. remains at the forefront of global innovation.

But that’s not everything. Besides the chance to rebuild our bridges, roads, and waterways, is an opportunity to rebuild the way we invest in our country, in our portfolios, and in ourselves.

Not a world of get-rich-quick, but one of long-term thinking, of diligent investments in solid companies that will yield real returns to investors, and real benefits to society.

Not a world driven by spin and narrative, but one that is building and investing in real things, real companies, real families, communities, and cities. Not a world of zero-sum thinking, but one where the effects of our stewardship will reverberate for decades to come, benefiting future generations of citizens and investors.

In his 1873 book Lombard Street, Walter Bagehot summarized the role of Central Banks as to ‘lend freely, to solvent firms, against good collateral, at high rates”, a phrase which became known as Bagehot’s dictum for its brevity and effect. New Constructs’ aim, similarly, is to “invest in real companies, with defensible moats, with strong profitability, at attractive valuations”.

We won’t get it right every time. We will, however, remain true to our investment philosophy regardless of what’s popular at the moment. We will continue to refine our process, our metrics, and listen to feedback in order to continue to improve and grow.

We won’t attempt to predict the future or be the next best market gurus – rather, we will focus on conducting the best possible fundamental analysis on the things we can control: the assessment of risk and reward. We’ll assess risk by measuring true profitability through Core Earnings, as well as making numerous adjustments to arrive at more accurate Balance Sheet and Income Statement figures. Just as importantly, we’ll estimate reward by comparing the expectations for future profits baked into market prices to identify opportunities with superior risk/reward and great candidates for long-term investments.

We hope you’ll join us on this journey.

So, how does all this affect which stocks we think are the best and the worst?

Get the full report for details.

2 replies to "The Best Stocks from our Rebuild and Renew Thesis"

Thanks for a thought-provoking article. I agree that the country’s infrastructure needs targeted infusions of capital, and certain companies are likely to benefit from the 3 recent federal bills.

Do the bills constitute a wise use of capital? That would be difficult for me to argue for any large federal spending bill given recent inflation, federal credit downgrades, and moves to replace the dollar as the world’s default currency. Personally, I see no reason to believe the 3 bills will decrease the wealth gap, improve productivity or significantly impact worldwide hydrocarbon emissions.

In the process of redistributing capital to preferred groups the bills will result in some needed infrastructure improvements. For ideological reasons, other infrastructure needs are not being addressed. For example, the reliability of our electrical grid will deteriorate as base-loaded (coal, hydro, natural-gas, oil & nuclear) power plants continue to be phased out. The grid in Mid- to Eastern-Tennessee should remain relatively robust, but I suspect both rolling and extended blackouts like those experienced in California and Texas will spread to other areas of the country.

Miscellaneous: 1) Some New Deal helped, but it took WWII to pull the US out of the great depression. 2) “As the world increasingly turns to electric and synthetic fuels, …” What do you consider to be an electric fuel?

Hi Eric,

This is a great question, would you mind asking it in the online community? I’ll ask an analyst to answer here, as well, but I think the wider community would have all sorts of different insights into these topics, as well.

Best,

Tam