This report is one of a series on the adjustments we make to convert GAAP data to economic earnings.

Reported earnings don’t tell the whole story of a company’s profits. They are based on accounting rules designed for debt investors, not equity investors, and are manipulated by companies to manage earnings. Only economic earnings provide a complete and unadulterated measure of profitability.

Converting GAAP data into economic earnings should be part of every investor’s diligence process. Performing detailed analysis of footnotes and the MD&A is part of fulfilling fiduciary responsibilities.

We’ve performed unrivaled due diligence on 5,500 10-Ks every year for the past decade.

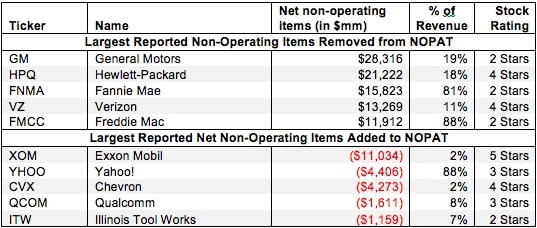

Most adjustments we have discussed thus far can only be found by performing careful footnotes research, but some of the adjustments we make use items commonly found in a company’s financial statements. We tend to write more on the footnotes items because we find them more interesting. Nevertheless, quite a bit of work has to be done to clean up income statements as well.

Income statement adjustments include financing items like interest expense/income, preferred dividends and minority interest income. These items are related to the financing of a company’s operations, not the operations themselves. We always calculate NOPAT on an unlevered basis.

Other income statement adjustments include any unusual income or expense, such as a gain on sale or restructuring charge.

6 replies to "Reported Net Non-Operating Items – NOPAT Adjustment"

Gross income is sales price of goods or property, minus cost of the property sold, plus other income. It includes wages, interest, dividends, business income, rental income, and all other types of income. Adjusted gross income is gross income less deductions from a business or rental activity and 21 other specific items.

Question about revenue recognition. Posted here due to the lack of a revenue section. How will you adjust for differences in company reporting in 2016 and 2017 as public companies adjust to FASB ASU 2014-09 Revenue from Contracts with Customers (Topic 606) issued May 28, 2014

Full Retrospective Method; A company must restate 2016 and 2017 financials when publishing its 2018 financials, i.e. the company needs to determine the impact of the new standard on its 2016 and 2017 financial statements

Cumulative Effect Approach; A company must determine the cumulative impact of the new standard in 2018 and book an adjustment to its 1/1/2018 retained earnings account.

Why are non-operating items added back to NI in the case of Hewlett Packard but the non-operating expense is included in Yahoo? Especially the restructuring charges.

Based on your examples:

HPQ:

NI + writedowns + Restructuring costs = – $12.7 bil + $18 + $2.3 = $7.6 bil.

YHOO:

Gain + interest and investment income – Restructuring = $4.6 bil. + $0.044 bil. – $0.236 bil = $4.408 bil.

In HPQ the $2.3 restructuring amounts were added ( I say “add” for the sake of math, to keep the signs the same) to the gain back but in YHOO the $0.236 bil restructuring amounts were “subtracted” from NI.

In both cases, restructuring expense is being added back to earnings. The difference is that in the Yahoo example, the non-operating expense is offsetting $4.6 billion in non-operating income, so we subtracted the restructuring expense from the non-operating gain to calculate the net non-operating income. Apologies if those examples were confusingly worded.

I understand the reasoning behind adding back (or at least not subtracting) restructuring charges to NOPAT. But why do you only add the after-tax asset write down part of the restructuring charges (excluding the severance costs) to invested capital? I’m referring to your DOW 2015 example.

Dan:

Great question! The reason we only add back the after-tax portion of the write-off is that the tax benefit of the write-off expense is a real cash benefit to the company. The idea is that the net amount of capital that we add back should exclude the tax benefit realized from the expense. Note that even though we remove the expense and the related tax benefit from NOPAT, the expense does reduce GAAP pre-tax income and the related tax obligation of the company in the period the expense is reported. So, there is a real tax benefit realized by the company for taking the asset-write-down expense. And, we recognize that tac benefit by reducing the amount of capital added back for the write-off by the value of the tax benefit.