In the wrangling over the Fiduciary Rule, regulators and financial institutions have overwhelmingly focused on the Duty of Loyalty, which requires advisors to give unconflicted advice. But, the Duty of Loyalty represents only half the equation. To truly protect investors, the Fiduciary Rule needs to address the Duty of Care.

The Duty of Care requires advisors to exercise an appropriate level of skill and diligence. Without the Duty of Care, the Duty of Loyalty is nearly worthless. An advisor that tries to act in your best interest, but doesn’t have the skill or diligence to do so can cause just as much harm as a conflicted advisor.

Despite this fact, there’s almost no evidence of significant resources invested in the enforcement—or even the definition—of the Duty of Care by regulators. A few thought leaders have stepped into the void, but without more guidance from regulators, it’s hard to know where the goal posts will be.

Duty of Care: Too Big To Fulfill?

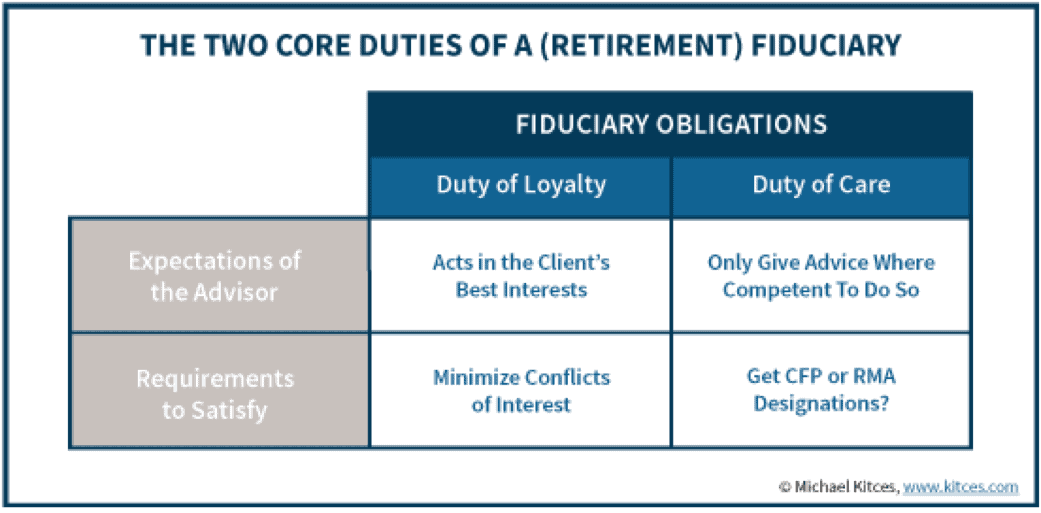

One of the biggest names in the business, Michael Kitces, weighed in on the potentially devastating class action lawsuit risks faced by financial institutions if they do not fully address the Duty of Care back in January. Specifically, Mr. Kitces asserts that:

“Financial Institutions could face a class action lawsuit … for systemically breaching the fiduciary duty of care by not sufficient training their advisors.”

On the heels of Mr. Kitce’s article, our Open Letter to the DoL specifically asked for guidance on how to fulfill the Duty of Care in its 3rd FAQ. Neither that FAQ nor the latest one released last week address the Duty of Care.

This ambiguity creates big question marks for firms that want to protect themselves from legal liability. Kitces proposes one potential solution: requiring all advisors to get CFP or RMA designations.

Figure 1: Is Michael Kitces’ Solution For Fulfilling The Duty Of Care Practical?

Sources: Michael Kitces: The DoL Fiduciary Class Action Lawsuit That Will Really Transform Financial Advice

Currently, only about 20% of all financial advisors have a CFP. Credentialing the other 80% would represent an enormous amount of time and effort, especially since only about 60% of those who sit for the CFP exam pass. The choice between undertaking this massive effort or being exposed to potentially devastating class-action lawsuits is a horrible one for any financial institution.

No Answer Is the Worst Answer

“In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.” Theodore Roosevelt

Given this conundrum, you’d imagine that regulators would want to provide clarity for institutions and advisors. Instead, the DoL has been quite vague in its comments about the Duty of Care. The only recent reference we found is in the first FAQ, where it cites the Prudent Man standard, which states that a fiduciary will act

“with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent man acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.”

This hypothetical “prudent man” represents an impossibly vague standard for advisors and investors. Cases such as GIW Industries, Inc. v Trevor, Stewart, Burton, & Jacobsen Inc. and Donovan v. Mazzola have brought a little clarity to the concept, but much ambiguity remains.

We are not sure why the DoL and, now, the SEC have not provided more guidance on how they will regulate/enforce the Duty Of Care. Perhaps, regulators and industry players see fulfilment of the rule as too big a problem to solve at this time. Perhaps, the status quo feels more secure. After all, if almost no one is fulfilling the Duty of Care, then, maybe, no one has to.

That sort of thinking is understandable in the face of the potentially enormous, if not impractical, task of getting official designations like the CFP or RMA for all financial advisors who need to meet a fiduciary standard of care.

It’s also understandable that firms might turn a blind eye toward the Duty of Care based on hope that a repeal or weakening of the Fiduciary rule will insulate them from responsibility to fulfill it. While a regulatory rollback of this sort is possible, it does not absolve financial institutions from having to prove to discerning constituents that they have the competency to provide a fiduciary level of service.

As we wrote in “Fiduciary Rule Delayed, But Its Impact Remains,” the debate around the Fiduciary Rule has already transformed the industry. Clients now want to know if their advisor provides a fiduciary level of service. Firms that can’t prove they can fulfill the Duty of Care will lose clients to those that can.

Making the Problem Smaller

Given the logistical and cost challenges of credentialing tens of thousands of advisors, we propose another approach for financial institutions to fulfill the Duty of Care. Our approach is vastly less expensive in terms of logistics and implementation. Rather than trying to accredit the advisors, we propose giving them research that enables them to fulfill the duty of care.

This research is probably necessary even if every advisor earned a CFP or RMA. As Kitces wrote in his post, “it’s the combination of competency education, and a prudence process, that is necessary for an advisor to substantiate that he/she actually met the fiduciary duty of care.” In other words, even if you have all the credentials in the world, you still need research to make informed investment decisions.

Research that fulfills the duty of care is not that hard to define. We think it is self-evident that research with the following qualities would equip an advisor to provide prudent advice:

- Comprehensive. It should reflect all relevant publicly available information (i.e. all 10-Ks and 10-Qs), including the footnotes and MD&A.

- Objective. Investors deserve unbiased research.

- Transparent. Investors should be able to see how the analysis was performed and the data behind it.

- Relevant. There must be a tangible, quantifiable connection to investment performance.

The average advice client would probably be surprised to learn that these criteria are not already required for investment research.

Research of this quality may not have been possible at scale in the past, but today’s technology makes it possible. Machine learning and natural language processing allow computers to do the heavy lifting of reading financial filings and analyzing data on the back end, freeing up human advisors to focus on their client’s individual needs.

In Nerd’s Eye View’s recent post, What Cyborg Chess Can Teach Us About The Future Of Financial Planning, Derek Tharp posits that the best advisors in the future will be those that are the best at leveraging technology. That idea certainly applies to the human advisors working with Robo-Analysts. The Robo-Analysts’ research makes advisors more effective than either a standalone human or robo-advisor in the same way that a human chess player aided by a machine is better than either one on its own.

What Should A Prudent Man Or Institution Do?

More thought leaders are beginning to turn attention to the Duty of Loyalty. MarketWatch’s retirement columnist, Robert Powell, recently echoed the concern over the lack of attention to the Duty of Care. He highlights Jeffrey Levine’s suggestion that financial institutions undertake a team oriented approach to advice to ensure they have access to the different pockets of expertise needed to provide truly comprehensive advice.

However, until we get more guidance from regulators, we cannot be sure of the expertise needed to fulfill the Duty of Care.

We agree and also believe that technology is key to the practical and cost effective fulfillment of the Duty of Care. More of the biggest names in the financial industry (see At BlackRock, Machines Are Rising Over Managers to Pick Stocks) are now embracing technology to leverage machines in the investment research process. Technology may be the only solution to the dual mandate for financial institutions: cut costs and fulfill the fiduciary Duty of Care.

Providing research as described above to advisors rather than undertaking a massive training effort is more cost effective in the short-term and better for investors in the long-term. Regardless of one’s level of training, high-quality research is necessary for fulfilment of fiduciary duties. It is only natural that we leverage technology to support human efforts in this area just as we have in so many other parts of modern society.

Regulators can aid this transition by providing clarity to everyone involved on how to fulfill the Duty of Care. Investors, clients, advisors and analysts deserve the latest in technology to get the diligence required to make prudent investment decisions.

This article originally published on August 9, 2017.

Disclosure: David Trainer and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

Photo Credit: GotCredit.com (Flickr)