It’s been a rough year for big IPO’s. Lyft (LFYT) is down almost 40% from its IPO price. Uber (UBER) is down 30%, and the vast majority of its early investors are underwater. Some smaller IPO’s – Beyond Meat (BYND), for instance – have done well, but the major public offerings have been flops.

Now, WeWork’s (WE: $20 billion rumored valuation) IPO process has gone so off the rails that it might not even happen. The company’s largest investor – the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank – has reportedly urged WE to shelve its IPO due to the poor response from investors. WeWork appears to have ignored SoftBank’s request and still plans to begin its roadshow next week.

The company is reportedly also considering governance changes in order to reassure investors. While a lower valuation and fewer conflicts of interest may be positive developments, this IPO still has many red flags. Investors should continue to stay away from WeWork no matter what the valuation is.

No Innovation in the Business Model – Just More Risk

WeWork was founded in 2010 in the SoHo district of New York City to provide co-working space, primarily for freelancers and small startups. In the nine years since its founding, the company has grown rapidly and consists of 528 locations in 111 cities and 29 countries.

While WeWork is growing rapidly, the service it offers is not new. The Belgian company IWG, which operates under the brand name Regus and a variety of other, smaller brands, utilizes the same business model of leasing office space, refurbishing it, and sub-leasing it under shorter terms to tenants.

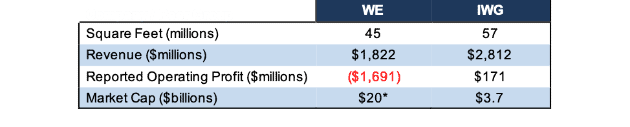

IWG has more square feet of office space than WeWork, earns more revenue, and actually earns a profit. However, IWG has a market cap of just $3.7 billion, still less than 20% of the reported $20 billion valuation WeWork is now seeking. The primary difference between the two is that WeWork describes its business model in the faux-tech lingo of “space-as-a-service” and its mission as “elevating the world’s consciousness.”

Figure 1: WeWork vs. IWG – Which Would You Buy

* Market cap for WE estimated from recent reporting

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Another difference is that WeWork operates with a much higher degree of risk by taking on significantly more operating lease commitments with longer terms and more geographic concentration.

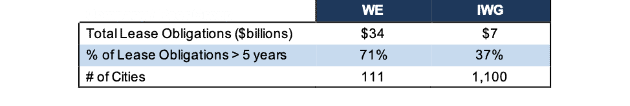

WeWork has ~20% less usable square feet of office space than IWG, but almost five times as many operating lease obligations at the end of 2018. Two main factors account for WeWork’s massive amount of operating lease obligations compared to IWG:

- Geographic Concentration: IWG’s locations are spread across over 1,000 cities all over the world. WeWork, on the other hand, operates in just 111 cities, and its S-1 reveals that the majority of its revenue comes from New York (where it is the largest office tenant in the city), San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Washington D.C., Boston, and London. WeWork’s concentration in high-priced cities means it pays significantly more per square foot than IWG.

- Longer Lease Terms: WeWork’s average lease term is 15 years. As Figure 2 shows, 71% ($24.1 billion) of its operating lease obligations are due in 2024 and beyond. IWG does not disclose its average lease term, but just 37% of its lease obligations ($2.5 billion) are due in 2024 or later. Taking on longer leases allows WeWork to get cheaper annual rents and offer premium office space at competitive prices. However, this long duration raises the risk that, during a downturn, WeWork will be locked into expensive leases and unable to find sub-tenants to cover its rental expense.

Figure 2: WeWork vs. IWG Business Model Carries More Risk and Leverage

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Making matters worse, the company currently uses an extremely high discount rate of 8.2% to calculate the present value of its operating leases on its balance sheet. This high discount rate allows the company to understate this liability, and it signals that the company faces a significant risk of default in a recession.

For comparison, IWG uses a discount rate of just 3.7%. The difference between the two company’s discount rates shows how aggressively WeWork has taken on extra risk to fuel its rapid growth.

Massive Recession Risk

WeWork’s business, essentially, aims to capture the spread between long-term and short-term rental costs. Landlords want stability and guaranteed cash flows, so they’re willing to lease office space at lower rates if a tenant is willing to make a long-term commitment, as WeWork does. Companies, on the other hand, want the flexibility of short-term leases that allow them to quickly grow, shrink, or move their office space in response to personnel needs. As a result, they’re willing to pay higher rents for this flexibility.

WeWork adds value to its office spaces in other ways – through renovations, technological support, and enhanced amenities – but the spread between long-term and short-term rents is at the core of its business model.

However, this model only works during times of economic expansion. When the economy enters a recession, companies lay off workers and reduce their office space. In this situation, short-term rents can decline to the point where they no longer cover the long-term rental expense.

IWG has managed to survive this recession risk by not locking itself into extremely long leases, diversifying its business geographically, and inserting provisions into many of its leases that allow for early termination, reduced rates, or other loss-minimizing provisions in the case of a downturn. WeWork, on the other hand, does not take any of these precautions.

Rapid Growth Not Delivering Profits

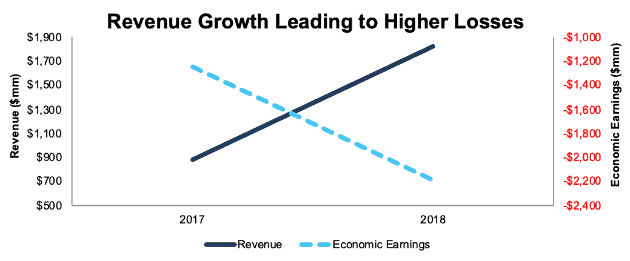

WeWork’s high-risk strategy has allowed the company to grow rapidly during the current economic expansion. Revenue increased from $886 million in 2017 to $1.8 billion in 2018, or 106% year-over-year, as shown in Figure 3. Economic earnings, the true cash flows of the business, declined from -$1.2 billion to $2.2 billion over the same time.

Figure 3: Revenue and Economic Earnings For WE: 2017-2018

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

We are currently in the midst of one of the longest economic expansions in U.S. history, one that has covered the entirety of WeWork’s existence. If the company cannot deliver positive cash flows now, when will it?

WeWork can’t blame its mounting losses on the costs of growth either. The company’s “contribution margin”, which excludes all sales and administrative expenses, along with non-cash location operating expenses, declined from 28% in the first half of 2018 to 25% in the first half of 2019.

WeWork is already getting farther away from profitability during what should be an ideal period for its business model. We shudder to think what the company’s losses will be when economic conditions worsen.

Corporate Governance Is Almost Nonexistent

Most recent IPO’s have already done away with any semblance of good corporate governance. Dual-class shares – which give total control to founders while preventing public investors from having a say – have become the norm. WeWork takes things a step further with three share classes, where Class B and Class C shares held by insiders have 20x the voting rights of shares sold to the public. This share structure gives founder and CEO Adam Neumann total control of the company for the foreseeable future.

What raises more red flags for WeWork’s IPO is Neumann’s significant history of personally profiting off his position in ways that raise significant conflict of interest concerns, including:

- Owning buildings where WeWork is a tenant. Neumann is his own company’s landlord and has collected rent from it for years. The company plans to address this clear conflict of interest by transferring Neumann’s holdings into a new entity called the Ark Master Fund (owned by WeWork) which will take ownership stakes in commercial real estate. Still, the fact that this obvious conflict was allowed to persist for so long raises serious questions as to how the company prevents similar conflicts from occurring.

- Borrowing from WeWork. The company has made multiple loans to Neumann personally and to his personal LLC (We Holdings LLC) at interest rates below 1%. These loans have all been repaid, but the below market interest rates suggest Neumann was getting a clear benefit.

- Employing family members. Neumann’s wife Rebekah Paltrow Neumann (cousin of Gwyneth Paltrow) is a co-founder of WeWork and serves as the CEO of the company’s education business, WeGrow. WeWork also employs another member of Neumann’s immediate family in a senior role, and it paid another family member to host events related to its “Creator Awards” in 2018.

- Charging for the “We” trademark. The most ridiculous case of self-dealing happened in July of this year as part of the company’s rebrand to “The We Company”. In order to rebrand, the company paid Neumann’s personal LLC $5.9 million in stock for the rights to the “We” family of trademarks. Neumann and WeWork subsequently reversed this transaction after blowback from analysts.

The reversal of this transaction shows that public investors do have some leverage to effect change in WE’s corporate governance. Still, it will take a much larger overhaul for WeWork to be able to earn investors’ trust.

Most notably, the company’s tri-class share structure means public investors will have no recourse to stop the self-dealing and personal profiteering that has marked Neumann’s tenure as CEO to date.

In fact, Neumann seems to be using the company’s IPO as another way to profit. Neumann has a personal line of credit of up to $500 million from UBS (UBS), JPMorgan (JPM), and Credit Suisse (CS), all of whom are coincidentally underwriters in WeWork’s IPO.

Interestingly, one bank not listed as a personal lender to Neumann is Morgan Stanley (MS), which reportedly pulled out of WeWork’s IPO after it failed to win the lead underwriter position, which instead went to JPM. One has to wonder if Neumann’s personal relationship with these banks influenced his choice of lead underwriter.

Neumann’s line of credit with the underwriters is secured by his holdings of WeWork stock. It also contains a margin call provision, which means that if the stock price declines to a certain point, the banks can claim and sell some of Neumann’s stock. This means if the IPO goes poorly, the underwriters themselves might become sellers and contribute to the stock price decline.

All of these factors – the tri-class shares, conflicts of interest, and unusual relationship with underwriters – suggest that this IPO is about Neumann and other insiders cashing in on the bubble-like valuation of WeWork’s shares and dumping the risk on public investors. If WeWork wants the capital it can raise in an IPO, it needs to address all of these issues in order to show investors it’s committed to creating long-term shareholder value.

What Is WeWork Worth?

At this point, trying to value WeWork feels like a fool’s errand. After all, it’s obvious the company’s valuation – whether it’s $47 billion or $20 billion – has no connection to its actual fundamentals or market opportunity. The disconnect between WeWork’s valuation and the $3.7 billion market cap of IWG makes this point very clear.

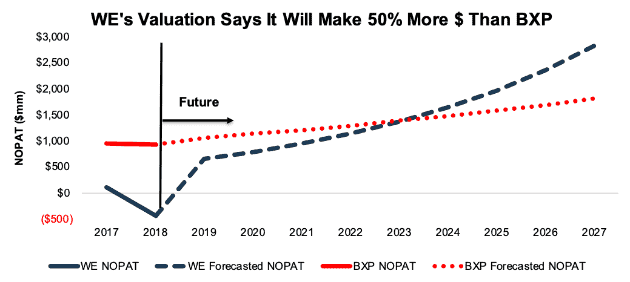

If we want to quantify the cash flow expectations implied by the $20 billion valuation for WeWork, we can’t benchmark performance expectations against IWG because it is too small. Instead, we have to look at larger firms, like the office REIT Boston Properties (BXP), that operate in the market WeWork ultimately aims to disrupt. As WeWork serves bigger businesses (40% of its users work for companies with more than 500 employees), it now competes with BXP and other traditional landlords.

In order to justify its $20 billion valuation, WeWork must achieve 30% NOPAT margins (similar to BXP) and grow revenue by 20% compounded annually for the next nine years. See the math behind this dynamic DCF scenario.

The private market expectations imply that WeWork will earn a 50% higher NOPAT than BXP – one of the largest office REITs in the world – by 2027. This seems like a highly optimistic assumption for a company with negative and declining NOPAT.

Figure 4: WE vs. BXP: Actual and Market-Implied NOPAT

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

While this scenario is less optimistic than what the company’s $47 billion valuation implied, we still don’t think it’s particularly realistic. It’s much more likely that when a recession hits, WeWork will collapse under the weight of its massive operating lease obligations, which increased from $34 billion to $47 billion in just the first six months of 2019.

If WeWork goes bankrupt, Neumann will already have cashed out to the tune of hundreds of millions, if not billions. The banks that underwrote the IPO will have collected hefty fees. The only losers will be the public investors that allow themselves to buy this overpriced and extremely dangerous stock.

Critical Details Found in Financial Filings by Our Robo-Analyst Technology

As investors focus more on fundamental research, research automation technology is needed to analyze all the critical financial details in financial filings. Below are specifics on the adjustments we make based on Robo-Analyst[1] findings in WeWork’s S-1:

Income Statement: we made $1.9 billion of adjustments, with a net effect of removing $1.2 billion in non-operating expense. We removed $362 million in non-operating income and $1.5 billion in non-operating expense. You can see all the adjustments made to WE’s income statement here.

Balance Sheet: we made $26 billion of adjustments to calculate invested capital with a net increase of $19.4 billion. You can see all the adjustments made to WE’s balance sheet here.

Valuation: we made $29.2 billion of adjustments with a net effect of decreasing shareholder value by $26.5 billion. You can see all the adjustments made to WE’s valuation here.

This article originally published on September 11, 2019.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

[1] Harvard Business School Features the powerful impact of research automation in the case study New Constructs: Disrupting Fundamental Analysis with Robo-Analysts.

1 Response to "Don’t Buy WeWork’s IPO At Any Price"

SoftBank Group recently disclosed WeWork’s valuation has fallen to just $2.9 billion – a far cry from the $7.8 billion valuation in September 2019 and $47 billion valuation the firm aimed for during its failed IPO.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-18/wework-s-valuation-has-dropped-to-2-9-billion-softbank-says