Check out this week’s Danger Zone interview with Chuck Jaffe of Money Life.

In our recent article “5 Charts That Prove We’re Not in Another Tech Bubble,” we show that today’s market valuation is about 75% lower than the 2000 peak. Focusing on economic instead of accounting earnings reveals that plenty of value remains. In addition, the 20% drop of Facebook (FB) after its disappointing projections shows that the market still cares about fundamentals.

Although the overall market looks reasonably valued, there are pockets of extraordinary risk where stocks with 2000-bubble-like valuations lurk. Specifically, there is a “micro-bubble” in certain tech stocks, where valuations reflect expectations for future cash flows that would require unrealistically high margins, growth, and market share. These expectations might not be so “bubbly” if not for the fact that the current margins and cash flows of these companies have trended at very low or negative levels for years.

Why We’re Not In a Macro Bubble

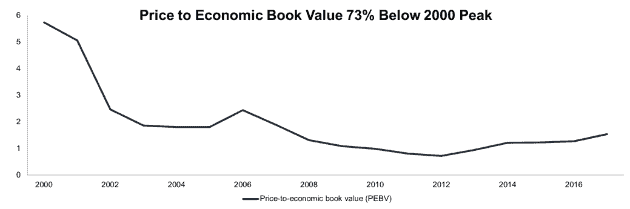

Figure 1 sums up the difference between the tech bubble and today’s market pretty clearly. It shows the price to economic book value (PEBV) of the largest 1,000 U.S. stocks by market cap going back to 2000. PEBV compares the current valuation of a company compared to the zero-growth value of its cash flows, i.e. NOPAT, so a higher PEBV means the market expects more future cash flow growth.

Figure 1: Price to Economic Book Value Since 2000

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

While the market’s PEBV has more than doubled since 2012, from 0.7 to 1.5, it’s nowhere close to its tech bubble level of 5.7.

There are definitely some outrageously valued companies out there, but those high valuations haven’t spread to the rest of the market. People forget that high valuations weren’t confined to tech stocks in the late 90’s. At the height of the tech bubble, Walmart (WMT) had a P/E ratio of 46 and a PEBV of 5.1. Currently it has a P/E of 30 (artificially inflated by a $3 billion loss on debt refinancing) and a PEBV of 0.9.

Bubble alarmists are hyping up the valuations of a subset of stocks while ignoring the rest of the market.

Macro-Bubbles vs. Micro-Bubbles

The tech bubble was a macro-bubble, a market-wide phenomenon that distorted the valuation of the entire market. Conversely, the current market has micro-bubbles or smaller groups of overhyped stocks trading at ridiculous valuations. So far, the hype has not spread to the entire market.

A few new features shape today’s market and explain why we will likely see more micro and less macro bubble for the foreseeable future:

- Politicians and Policymakers Focused on Preventing Macro Market Crashes: Today’s politicians and policymakers are heavily shaped by both the housing bubble of the mid-2000’s and the tech bubble of the late-90’s. They will likely do everything in their power to prevent recurrence of such cataclysmic events on their watch.

- Rising Influence of Noise[1] Traders: Noise traders, who make investment decisions based on noise and have no regard for fundamentals, are an increasingly influential force in today’s market. Roughly a quarter of all U.S. adults with internet access are retail online traders. That’s around 50 million investors who don’t have professional trading (much less investing) experience and might be more susceptible to buying into “story” stocks without understanding the fundamentals. There’s power in those numbers.

- Overhyping of “Transformative” Technology: The splintering of online media has led journalists to overhype nearly every new technology and trend in a relentless competition for clicks. For example, despite the “Retail Apocalypse” narrative, brick and mortar sales still account for 90% of retail sales, and Walmart earned nearly three times more revenue than Amazon (AMZN) last year. In reality, very few new technologies are as transformative as we like to imagine.

- Value Transfer vs. Value Creation: Too many investors overestimate the value creation opportunities for new technologies. Even when technologies are transformative, predicting who will reap the benefits of these technologies is difficult. Often, most of the value accrues to end users/consumers and not corporations. When it does accrue to a company, it’s usually at the expense of another company. During the tech bubble, bulls believed that the internet would make our economy radically more productive and allow the ~5% GDP growth rate of the late 90’s to persist for many years. When this utopian future failed to materialize, the market collapsed. By contrast, today’s micro-bubble companies compete against firmly established incumbents from which they must take large chunks of market share to survive. Instead of adding value, these companies aim to take value from existing players. Even if they succeed, we think much of that value will eventually pass to consumers.

This last point is key. In 1999, investors gave Microsoft (MSFT) its absurdly high valuation because they believed its software would create enormous amounts of value and growth for thousands of other companies. On the other hand, Tesla’s (TSLA) sky-high valuation implies that it will take market share away from General Motors (GM) and Ford (F), which decreases the valuation of those companies.

These modern-day, micro bubbles reflect the zero-sum nature of today’s crowded and more mature competitive landscapes.

Stocks in Micro-Bubble #1

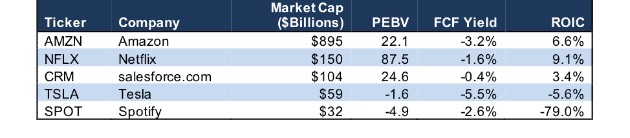

Figure 2 lists the five tech stocks we put in our first micro-bubble. They share a few key characteristics:

- Low or negative return on invested capital (ROIC) and free cash flow

- Unrealistically high valuations: all ten companies either have negative economic book values, or they have a PEBV above 20

- Expectations that they achieve heretofore unseen dominant market shares

Figure 2: Micro-Bubble Stocks

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

These are five of the largest micro-bubble companies. In future reports, we’ll cover companies that are attempting to take over smaller niches of the economy.

Below, we run briefly through what makes each of these companies part of the micro-bubble.

Amazon (AMZN)

Fun fact: Amazon’s $885 billion market cap is higher that Walmart, Home Depot (HD), Oracle (ORCL), and Disney (DIS) combined. Investors are betting that Amazon can grow to dominate multiple industries while earning significantly higher margins than it does now.

Amazon has finally shown an ability to earn a profit, but it still must grow NOPAT by 30% compounded annually for 19 years to justify its current valuation. See the math behind this dynamic DCF scenario. For comparison, only 6 companies in the S&P 500 managed to grow NOPAT by 30% compounded annually for just the past ten years. Maintaining that growth rate for nearly double that timeframe would be an extraordinary feat.

Amazon prefers to point investors to free cash flow, but its reported free cash flow numbers are an illusion. In reality, the company continues to experience significant cash outflows.

Investors who focus on understanding true cash flow and fundamentals know the disconnect between actual cash flow and the market’s expectations for future cash flows borders on the absurd.

Netflix (NFLX)

Netflix has become one of the leading creators of original content, but it’s done so with an unsustainable cost structure. As this excellent video from The Ringer explains, Netflix earns an accounting profit, but only because its reported content costs understate its actual content spending by ~50%. The company continues to lose billions of dollars a year and grows increasingly dependent on the high-yield debt market.

Felix Salmon of Slate recently published a piece titled “Netflix Can Either Become the Dominant Media Monopoly of the 21st Century or Go Bust.” The market values Netflix as if it will be that dominant monopoly when, frankly, there’s a very good chance it goes bust. Risk/reward for this stock is so bad that no investor with any respect for fundamentals can own this stock in good conscience.

Salesforce.com (CRM)

Salesforce has racked up losses for years while pursuing growth at any cost. The theory behind this strategy is that the company will eventually be able to cut back heavily on its marketing and R&D costs while maintaining its recurring revenue stream.

Even if this strategy does work, which is far from certain, the company is currently valued at 10 times revenue, or double the valuation of Oracle. This hasn’t dissuaded bulls, as Salesforce generates classic tech bubble-style headlines like “Ignore Salesforce’s Valuation.” In other words, they want investors to ignore fundamentals.

Tesla (TSLA)

Tesla currently has a higher market cap than GM despite selling ~1% as many cars in 2017. What’s more, GM is already ahead of Tesla in self-driving technology and rapidly catching up when it comes to electric vehicle production.

Elon Musk keeps promising that Tesla will revolutionize the auto industry, but so far Tesla hasn’t shown an ability to navigate the manufacturing logistics that the established automakers figured out decades ago. The company’s valuation is blind to fundamentals and seems entirely focused on the cult of personality that has built up around Musk.

Spotify (SPOT)

Spotify wants to disrupt the music industry, but so far it remains beholden to the Big 3 record labels that own 85% of the music streamed on its platform. The market thinks of Spotify as a trendy tech company, but as we wrote in our report on the stock, the economics of its business are more similar to the movie theater industry.

Spotify’s leverage against the record labels is further weakened by the rapid growth of competitors like Apple Music (AAPL). It’s hard to see how Spotify can justify the growth expectations implied by its valuation unless it could pull off the unlikely feat of taking over ownership of its content from the labels while holding off competition from other streaming services (all without having to overspend like Netflix has).

Again, we see a company where the valuation reflects the best-case scenario with little to no tether to fundamentals.

How to Bet Against the Micro-Bubble

Investors that want to bet against these micro-bubble stocks can short them directly, but that can be expensive and risky for these momentum-driven companies. As the saying goes, the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

Another way to profit from the busting of this micro-bubble is to invest in the incumbents from which these companies must take major chunks of market share. Much of the valuations of micro-bubble stocks depend on these firms’ ability to take market share away from existing players. When these stocks fall back to earth, a great deal of capital should be reallocated to the incumbents.

Our next report on this topic, “Micro-Bubble Winners”, highlights some of our favorite stocks to buy as a bet against this micro-bubble. Subsequent reports will highlight micro-bubble stocks in industries such as payments, social media, and real estate.

This article originally published on August 6, 2018.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

[1] Shiller, Robert J., et al. “Stock Prices and Social Dynamics.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, vol. 1984, no. 2, 1984, pp. 457–510. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2534436.