Corporate profits are near an all time high. Public companies have nearly $2 trillion in cash just sitting on their balance sheets. Corporate America has the resources to deploy a large amount of capital and invest in new technologies and innovations that can drive growth.

Instead, they just keep spending more and more money on buybacks. 1,900 companies have spent money on buybacks and dividends since 2010, and the combined return of capital to shareholders for those companies equals 113% of capital spending, according to Reuters.

Many people view buybacks as a good thing. In addition to being a vehicle for returning cash to shareholders, they reduce the total number of shares outstanding, so they should increase the value for the remaining shareholders, right? In certain cases, that’s true. There are buybacks that make sense from a capital allocation standpoint and serve the best interests of investors. Unfortunately, these tend to be the exception rather than the rule.

Most buybacks are carried out for reasons that have nothing to do with maximizing shareholder value. Pressure to hit short-term earnings targets and executive compensation plans that incentivize the wrong metrics often push companies to buy back stock when it’s most expensive and the capital could better be used elsewhere.

Companies Buy Back Shares At Peak Valuations

In theory, corporations should have a distinct advantage over the rest of the market when buying back their shares. Executives know their industry, the challenges the company faces, and their strategic plans better than anyone else, which should enable them to buy their stock when it’s cheap and not when it’s overvalued.

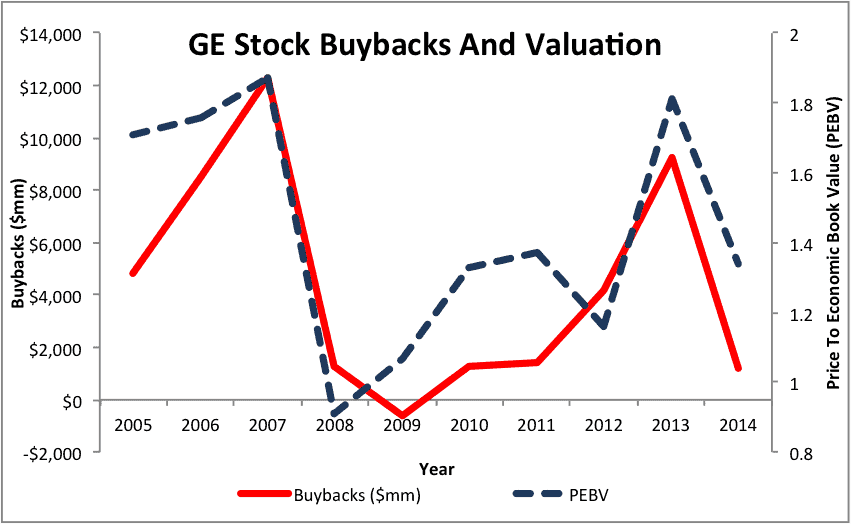

Instead, the data shows that companies buy back more stock during booms and sell them when the market crashes. In this way, they act like panicky and underperforming investors. Figure 1 shows this value-destroying behavior in action for GE (GE) by comparing between the amount of money spent buying back shares and the price to economic book value (PEBV), a measure of the growth expectations embedded in the stock price.

Figure 1: GE Buys Its Own Shares At The Worst Possible Times

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings.

As Figure 1 shows, GE bought back an incredible $12.3 billion worth of stock in 2007, right before the market crashed. Then in 2009, at the start of a major bull market, the company sold $600 million worth of its own stock. Throughout the past decade, there is a high correlation between how expensive GE’s stock is versus current cash flows and how much stock the company repurchases.

Overall, GE bought back almost $44 billion of its own shares (17% of its market cap) in the past decade. Over the same time, its stock has fallen by 15%. By inefficiently utilizing valuable capital to buy back stock at inflated prices, the company destroyed value for long-term shareholders.

The Overvaluation Trap And Executive Compensation

GE’s long-term shareholders have suffered in part because the company’s executives are responding to short-term pressures. In particular, they seem to have responded to what the Harvard Business Review calls “The Overvaluation Trap.”

When a company’s equity becomes overvalued, its executives have to scramble to try to justify that expensive price. One way to do that is by artificially boosting EPS through share buybacks. GE appears to have done this very effectively, as the company has managed to hit or beat EPS expectations in 15 out of the past 16 quarters.

In addition, many companies have executive compensation plans that incentivize excessive share buybacks, either directly or indirectly. For instance, a percentage of GE executive bonuses depend on the company returning a certain amount of cash to shareholders. In 2014, executives had to make sure combined dividends and buybacks hit at least $10 billion to get their full bonus, even if that decision made no sense from a strategic perspective.

Other companies incentivize share buybacks by emphasizing metrics that can be easily manipulated and have little impact on shareholder value. For instance, executives at Cisco (CSCO) are judged in part on their ability to grow adjusted operating income, adjusted EPS, and operating cash flow.

That word “adjusted” is crucial. The metrics CSCO uses for judging executive performance exclude share-based compensation. That means executives can pay employees (and themselves) with stock instead of cash, buy back shares to offset the dilution, and increase these adjusted metrics without doing anything to improve real operating performance.

In 2015, CSCO bought back 155 million shares, but after the effects of employee stock compensation it only reduced the total shares outstanding by 38 million. All those buybacks are just accounting trickery that executives use to boost their own bonuses.

The Opportunity Cost Of Buybacks

We know buybacks tend to destroy shareholder value by using capital to buy an overvalued asset. However, that’s only half of the equation. The cost of buybacks don’t just come from the losses on overpriced stock, they also come from the missed opportunities to invest in growth and innovation.

For instance, AT&T (T) has bought back nearly $50 billion in stock over the past decade. That’s money that could have been used to improve the quality of its wireless network and catch up with Verizon (VZ). All those buybacks have not kept AT&T from underperforming versus the broader market and VZ (which rarely buys back stock) over the past five and ten years.

We tend to think of buybacks as a sign of success, proof that the company has plenty of cash to throw around. In reality, they amount to an admission of failure. A company that buys back its stock is signaling to the market that it lacks profitable opportunities for investment.

Not All Buybacks Are Bad

Even if with all those concerns, buybacks do make sense under certain specific conditions:

- The stock should be trading at a PEBV below 1, meaning the company is buying back shares for cents on the dollar.

- The company’s balance sheet and free cash flow should be strong enough to support the buyback without jeopardizing future liquidity or investment opportunities.

- The company should have more cash than it does profitable investment opportunities.

One company that meets all three criteria is Oracle (ORCL). In 2015, ORCL bought back $8.1 billion in stock (5% of market cap), reducing shares outstanding by nearly 120 million. ORCL’s shares currently trade at a PEBV of 0.9, meaning it’s buying back shares at a 10% discount to their zero-growth value.

With $50 billion in excess cash on the balance sheet and $9 billion in annual free cash flow, ORCL has more than enough cash on hand to support its buyback program, and more than it could reasonably hope to invest profitably in the near term.

Not only do these buybacks serve the interests of shareholders, they’re also good for the overall economy. When a company with excess cash and few investment opportunities buys back its stock, it puts that cash back in the marketplace for individual investors to distribute to companies that have a need for capital.

In buying back billions of dollars worth of stock last year, ORCL retired its shares cheaply without compromising its ability to invest in future growth. Unfortunately, the majority of companies buying back stock today are not in the same situation.

Disclosure: David Trainer and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

Photo Credit: gotcredit.com (Flickr)

3 replies to "How Buybacks Destroy Shareholder Value"

Very useful info, thank you!

Thank you!

I agreed with the danger caused by the pratice of buying back shares , when they are selling above intrensic value. Simply Following the cash flow satement we can simple see that somthing is profoundly wrong. 1) It compenstes the menagers bonus 2) It destroys value for the shares holders, ant to the cororation both at the same time. In my humble opinion, it will be the N1 candidate for the next stock market crash.