At this point, it’s nearly impossible to argue with the notion that earnings manipulation is prevalent throughout the ranks of publicly-traded companies. We know that CFOs have admitted to manipulating earnings and the ongoing Valeant Pharmaceuticals (VRX) scandal continues to expose the creative ways companies can artificially boost results.

While most earnings manipulation is not as blatant as Valeant, the fact remains that investors have to be on the lookout for earnings management at all times. To be properly vigilant, it’s important to understand why executives misstate earnings. When you understand the why, you’ll have a better sense of what you need to look for.

- Their Bonuses (And Jobs) Depend On It

Ever since “performance-based” bonuses were made tax-deductible in 1993, an increasingly large portion of executive compensation has been tied to hitting certain performance targets. In many cases, these are “adjusted” non-GAAP metrics that are designed for CEOs to always hit those incentive targets. In other cases, the targets are simply so low that it would be almost impossible to miss them.

Still, occasionally executives will see their bonuses get cut if they miss targets for metrics like revenue and EPS growth, so there’s an incentive in place for them to do whatever it takes to meet that target. That could mean things like channel stuffing to boost revenue at the end of a quarter, lowering reserves to artificially boost EPS, or even lumping regular expenses into one-time items such as “restructuring” so that they’ll be excluded from the earnings calculation.

There are almost too many options to count. In 2014, Caleres (CAL) hit an adjusted EPS of $1.72, 11% above the target threshold to receive their full bonuses. However, this number was inflated by:

- A $2 million decrease in the company’s inventory reserve

- Unrealistic pension plan assumptions, which included an expected return on plan assets of 8.25% and a discount rate of 5%, which allowed the company to earn $10.7 million in net periodic benefit income.

Together, these two non-operating items boosted CAL’s income by $0.29/share. Removing that impact, the company would have had an adjusted EPS of $1.43, which would have fallen short of the performance target. Boosting earnings to hit those targets helped the five highest paid executives earn record compensation of $18 million last year, or 15% of after-tax profit (NOPAT)

Of course, the risk for executives who miss earnings targets can be even greater than just losing money from their bonuses. Studies have shown that simply missing targets can increase a CFO’s chance of getting fired, even if they just barely miss and the stock still does well!

With the extreme focus on these quarterly and annual targets, it’s no wonder that executives give in to the pressure because those that don’t earn less in compensation and are at a higher risk of getting fired.

Win More Assets, Keep More AUM, Avoid Regulators’ Scrutiny

Learn more today and sign up now!

- They Want To Lower The Bar

One of the most interesting details from the CFO survey linked above is the fact that roughly 1/3 of the cases of earnings misrepresentation actually involve companies decreasing their earnings. Decreasing earnings seems counterintuitive at first, but it makes more sense when you remember that it’s more important to the executives whether or not they hit their targets rather than by how much.

Therefore, if an executive is on track to beat their target by a wide margin, they might actually want to decrease their earnings, thereby setting up an easy comp the following year. One of the most common tactics for accomplishing this goal is to increase reserves. Executives can decrease earnings by inflating reserves. Then, if the company is struggling to hit their target in a later period, the executive can always decrease those reserves back down and book the decrease as positive income.

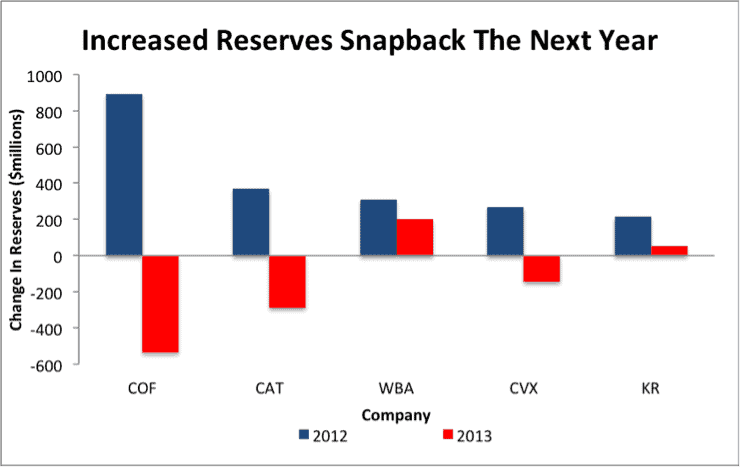

Figure 1 shows the results of the work we did on reserves in 2013. In 2012, the companies that increased their reserves the most—thereby decreasing reported income—were Capital One Financial (COF), Caterpillar (CAT), Walgreen’s (WBA), Chevron (CVX), and Kroger (KR). The next year, three of those five companies significantly decreased their reserves, while the other two increased them by a much smaller amount.

Figure 1: 5 Companies With The Largest Increase In Reserves In 2012

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings.

If you just looked at reported income, it would have seemed like Capital One grew steadily in 2012 and 2013. In reality, by reversing the impact of change in reserves, we see that it grew NOPAT by over 100% in 2012 and then declined in 2013. By changing reserves, executives managed to show two years of growth rather than one great year and one struggling year where their bonuses would get cut.

- Everyone Else Is Doing It

Since measures of executive performance are so often based on comparisons to a company’s peer group, it creates a sort of arms race of financial manipulation. As soon as one company in an industry starts manipulating their numbers, everyone else has to follow suit or get left behind.

A recent study looking at restatements from over 2,000 companies found that there was a strong tie between whether one company manipulated earnings and the percentage of firms in its region or industry that had announced restatements in the past year. Simply put, when executives see their competitors engaging in accounting trickery, they tend to follow suit.

The good news? The study found that when there was significant enforcement action, shareholder litigation, or negative press, the copycat effect didn’t occur. When executives are held accountable for manipulating earnings, their peers don’t tend to follow them. The bad news is that…

Win More Assets, Keep More AUM, Avoid Regulators’ Scrutiny

Learn more today and sign up now!

- Executives Face Very Little Accountability

Executives rarely face much blowback when they misstate earnings, either from regulators or the investing public. On the regulatory side, enforcement is so weak that they rarely even have to give back the bonuses they earned from false earnings.

How crazy is that? Executives get paid massive bonuses for hitting growth targets, and then when it’s revealed they didn’t actually hit those targets, they get to keep the bonuses anyway! So much for being aligned with shareholder interests.

Investors and analysts don’t do much better. Sell-side analysts, who have a vested interest in maintaining a good relationship with the companies they cover, don’t tend to probe too deeply into reported earnings.

“The sell side has no incentive to detect earnings quality,” said one anonymous CFO who was interviewed for the survey on earnings misrepresentation.

Buy-side analysts and short-sellers tend to be better at detecting these red flags, but too often they get shouted down when trying to raise the alarm. Take the blowback Andrew Left of Citron Research has faced for calling out Valeant. As the stock has fallen, the executives and large investors with a vested interest in supporting those misleading earnings have accused him of “playing on the fears of investors”.

This has led to a bizarre culture where executives manipulate earnings to reward themselves with bigger bonuses, and everyone knows this is happening, but when anyone tries to call them out on it they get accused of being greedy and self-serving.

The activist investors who might be best positioned to curb executive bonuses rarely do anything about them. Pershing Square founder Bill Ackman actively encouraged the aggressive acquisition accounting at Valeant that helped executives nearly triple their compensation in 2014, and he has been a staunch supporter of the executive team at Jarden (JAH) that uses an exec friendly form of adjusted earnings to help executives boost their own pay at the expense of shareholders.

Ideally, this situation will change at some point, and the correct enforcement mechanisms will be in place to prevent earnings manipulation. Until that time, investors need to be aware that the reported results they’re looking at are not necessarily an accurate indication of the underlying economics of the business. It takes a lot of work to reverse all the loopholes that executives exploit to serve their own purposes.

Disclosure: David Trainer and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

2 replies to "4 Reasons Executives Manipulate Earnings"

nice article…value retailers are suffering the most

Thank you. Excellent information!