This report is one of a series on the adjustments we make to convert GAAP data to economic earnings. This report focuses on an adjustment we make to convert the reported balance sheet assets into invested capital.

Reported assets don’t tell the whole story of the capital invested in a business. Accounting rules provide numerous loopholes that companies can exploit to hide balance sheet issues and obscure the true amount of capital invested in a business.

Converting GAAP data into economic earnings should be part of every investor’s diligence process. Performing detailed analysis of footnotes and the MD&A is part of fulfilling fiduciary responsibilities.

We’ve performed unrivaled due diligence on 5,500 10-Ks every year for the past decade.

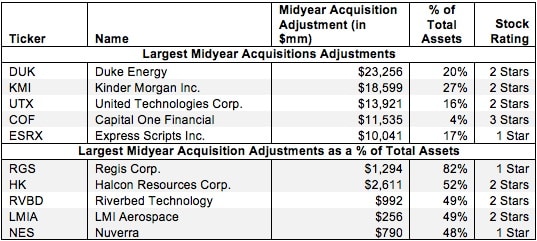

When a company makes an acquisition, the entire purchase price is added to the company’s balance sheet in the year of the acquisition along with any assumed debts or other long-term liabilities. However, the only income added to the income statement is that which occurs after the acquisition closes. In other words, the balance sheet is charged with the full price of the acquisition while the income statement only gets partially impacted.

Except for the rare event that an acquisition closes on the first day of the fiscal year, one must adjust for this accounting mismatch of income vs capital deployed when calculating return on invested capital (ROIC).

To ensure an accurate measurement of cash-on-cash returns, we adjust invested capital to reflect the time-weighted value of the acquisition. This adjustment is necessary to ensure the impact of the acquisition on NOPAT is commensurate with its impact on invested capital.

6 replies to "Midyear Acquisitions – Invested Capital Adjustment"

Hello,

Superb website. This website has the best writing on the internet I have seen on notes to the financial statements and how to do adjustments.

So the idea behind this particular adjustment is to do this:

Invested capital – Full Price of Acquisition + Time weighted value of acquisition.

In your Duke Energy example, then, we should do this:

Invested capital – 45 + [ (45) * (182/364) ] = Invested capital – 45 + 22.5

This way we undo the mismatch between the I/S and B/S and include only the time weighted value of IC that is economically on par with the current NOPAT generated by the subsidiary.

I assume this is also what you meant by we reduce invested capital (thereby inc. ROIC) because we are eliminating the entire full price of the acquisition and replacing it with only the time weighted value.

Is this correct?

I am new to some of these adjustments from notes to the financial statements and am trying to thoroughly understand each one.

How does the adjustment decrease invested capital when you added the time adjusted total value of the acquisition to invested capital in both the Duke Energy and Riverbed Technology examples?

Adj. = Invested capital + time adjusted value of acquisition

Adj.= Invested capital + [Purchase price + debt + other long term liabilities]*[n/364]

This higher invested capital should decrease ROIC, not increase it. The only way ROIC increases is if the full price of the acquisition is removed from the B/S (thru invested capital) and is then replaced with the ‘partial value’ (time adjusted value of acquisition).

Am I understanding this right?

I should clarify that the midyear acquisition adjustment only impacts average invested capital, which is the number used to calculate ROIC. Year end invested capital is not impacted by this adjustment.

In the case of Riverbed, it’s not that we’re removing the acquisition, we’re just time-weighting those assets in our calculation of average invested capital to ensure that we get an accurate picture of the impact they had on the company’s operations for the year. For companies that make a large acquisition late in the year, this adjustment significantly decreases average invested capital versus a simple average of the beginning and ending invested capital.

Ok I remember now from another webpage of NC’s.

Avg. incremental non-acquired Invested capital = [ Ending IC – Beg. IC – Acquired Invested Capital ] /2. This particular webpage describes the acquired invested capital part, thus total avg. invested capital should decrease and ROIC increases. got it.

Thanks!!!! Deeply appreciate your fast responses.

copied the wrong formula.

Figure 1: How to Calculate Average Invested Capital

Beginning Invested Capital + (Ending Invested Capital – Acquired Invested Capital) / 2) + Time Weighted Acquired Invested Capital.

correction: meant to say this webpage describes the time weighted acquisition part.