“Together, Men’s Wearhouse and Jos. A. Bank will have increased scale and breadth, and Jos. A. Bank’s strong brand and complementary business model will broaden our customer reach. We expect the transaction will be accretive to Men’s Wearhouse’s earnings in the first full year.”

-Men’s Wearhouse CEO Doug Ewert, announcing the acquisition of Jos. A. Bank on March 11, 2014

“What we did not know then but do now was just how toxic some of the promotions were and how deep and far reaching the transformation required would be. And how significantly near term performance would suffer as we began to execute painful but necessary steps to restore the long-term sustainable profit model.”

-Ewert in a quarterly conference call to shareholders, December 10, 2015

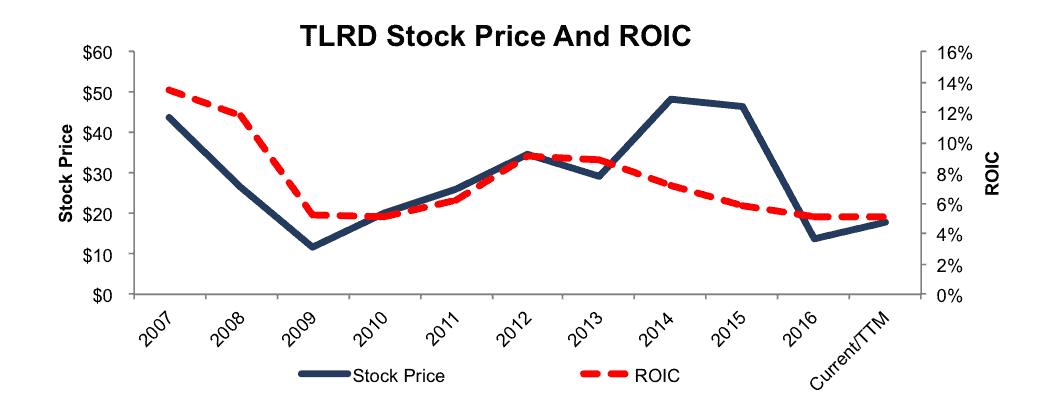

It’s been a challenging year for Tailored Brands (TLRD), the holding company formed out of the merger of Men’s Wearhouse and Jos. A. Bank. Lower than expected synergies and challenges with integrating the brands have hurt operating performance and sent the stock tumbling over 70%. As Figure 1 shows, the impact of this failed acquisition in terms of both stock price and return on invested capital (ROIC) was similar to the ’08 recession.

Figure 1: Jos. A. Bank Acquisition Destroys Value For Investors

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings.

Last February we warned investors of the risks this acquisition carried. Management’s synergy assumptions were guided by misaligned compensation incentives and were far too optimistic.

Why Executives (Shamelessly) Want To Acquire

The acquisition of Jos. A. Bank by Men’s Wearhouse was especially unique because it originally looked as if the deal would be the other way around. This whole saga began in September of 2013 when Bank launched an unsolicited, $2.3 billion bid to buy Men’s Wearhouse.

When their company was the one about to be acquired, Men’s Wearhouse executives and board members saw all sorts of risks. They rejected the deal, citing antitrust concerns, risks, and a buyout price they felt undervalued the company.

Just a month later, Men’s Wearhouse executives changed their tune and saw great strategic opportunity, only with them as the acquirer. After a few months of haggling where the price increased from $1.2 billion to $1.8 billion (and in which Jos. A. Bank tried to scuttle the deal by acquiring the parent company of Eddie Bauer), the two sides finally reached an agreement in March.

It’s not hard to see why Men’s Wearhouse executives wanted to be the ones doing the acquiring rather than getting acquired. While a number of Jos. A. Bank executives left as part of the acquisitions, Ewert saw his compensation increase by 167%, to $9.7 million. He even earned a special bonus specifically for the acquisition.

Executives seek and execute acquisitions that have little to do with shareholder value because they help boost metrics such as sales, EPS, or EBITDA that determine their bonuses. In addition, a big acquisition will put the company in a peer group with larger competitors, which also tends to boost executive pay. See Danger Zone: Compensation Committees for details on how these misaligned compensation incentives arise.

It’s hard to imagine these incentive structures didn’t impact the decision of Men’s Wearhouse to reject the lucrative buyout offer from Jos. A. Bank in favor of a much riskier and value-destroying deal for shareholders.

How Companies Overstate The Benefits Of Acquisitions

As we discussed in our original report, the economics of this acquisition never made sense. Jos. A. Bank earned an after-tax operating profit (NOPAT) of $63 million the year before the acquisition. At a buyout price of $1.8 billion, the ROIC of the deal was just 4%, below Men’s Wearhouse’s cost of capital (WACC), which was 8% at the time.

Worse yet, Bank was already struggling with slumping sales and the thin margins brought about by the “toxic” promotions Ewert mentioned. As a result, management had to promise impressive results to make the deal seem worthwhile to shareholders.

Notably, they promised $100-$150 million in synergies annually from “improving purchasing efficiencies, optimizing customer service and marketing practices, and streamlining duplicative corporate functions.”

Those promises are nice, but without more details and models on exactly how those synergies would be achieved, investors are left with no choice but to rely on a management team that does not share their best interest. After all, synergies were key to the credibility of the acquisition, and shareholders should have more detail on how exactly these synergies would be achieved so they can judge the feasibility of the plan.

As it stands, TLRD recognized just $50 million in synergies over the past year, and while they still claim these synergies will eventually reach the lower end of that $100-$150 million range by the end of this year, it’s hard to trust those claims given the combined company’s poor operating results.

More importantly, the expectation that Men’s Wearhouse could just “fix” Jos. A. Bank’s heavy promotional structure—the company may be best known for its former “Buy 1 Suit, Get 3 Free” deal—has proven to be false. Attempts to end these promotions drove customers away and sent comparable-store sales down 32% in the most recent quarter.

Simply put, Men’s Wearhouse executives sold this acquisition to shareholders under a naively best-case scenario, assuming that they could instantly recognize significant cost savings and turn around a struggling business. There was no other way they could justify the $1.8 billion price tag and get those big bonuses.

Nearly $800 million of that $1.8 billion was attributable to Goodwill, which represented the “growth opportunities and expected synergies” of the acquisition. As we’ve written before, large amounts of Goodwill represent a risk factor for significant write-downs in the future.

Sure enough, last year TLRD wrote down the entirety of the Goodwill attributable to Jos. A. Bank, acknowledging that the “growth opportunities and expected synergies” were essentially worthless. Surprised?

Integration Is Difficult And Expensive

Not only do misguided incentives cause executives to overstate the benefits of large acquisitions, they also push them to underestimate the challenges in combining two large entities.

Acquisitions are hard to execute. The logistics of combining two workforces, supply chains, and corporate cultures into a single, efficient company are staggering. Entire offices have to be moved. Processes need to be rewritten. It can take years of painstaking review to figure out what to take and what to leave from each company, and even longer to implement those changes across the entirety of the operations.

As TLRD has learned, those challenges can be even more daunting in the retail sector. Consumers are fickle; they don’t like it when their shopping experience changes. Jos. A. Bank’s promotional strategy may have been an illogical business model, but its customers had grown attached to it. Changing it drove them away.

Another Example Of A Bad Acquisition

There are plenty of other examples of failed retail acquisitions. In 2012, Ascena Retail Group (ASNA) paid $890 million for specialty women’s retailer Charming Shoppes. Both companies already managed a large portfolio of brands, and trying to integrate and manage all these disparate brands proved too challenging. Since the acquisition, ASNA’s ROIC has fallen from 10% to 2%, and its stock price is down 50%.

More recently, Dollar Tree (DLTR) paid $9.1 billion to acquire struggling Family Dollar (FDO). When FDO first put itself up for sale, we argued that no company should want to acquire it, and recent results bear that out. DLTR has struggled to integrate FDO so far, and sales results have been far below expectations.

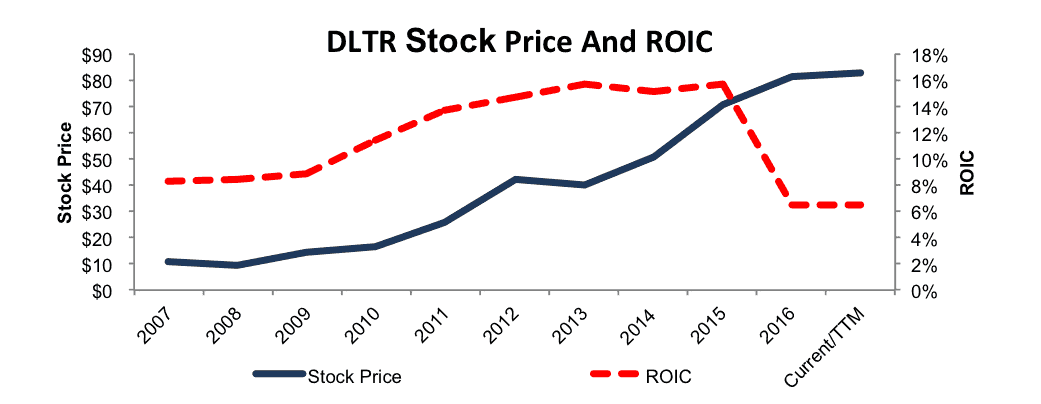

The acquisition was completed in July of 2015. For the full year 2015, DLTR’s ROIC fell from 16% to 6%. As Figure 2 shows, this decline is especially shocking because DLTR’s business had been strong up to that point.

Figure 2: Acquisition Hurts Previously Strong ROIC

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings.

DLTR had a profitable and growing business that had generated fantastic returns for shareholders and looked set to continue to do so for many years to come. With the acquisition of FDO, the company torpedoed its ROIC, took on an extra $11 billion in debt that will limit its ability to invest in new growth opportunities in the future, and made it more difficult to focus and execute on its core business.

DLTR’s stock price has not followed its ROIC down yet, but we expect a significant drop to come soon as the adverse affects of this acquisition become more apparent to investors.

Disclosure: David Trainer and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

Photo Credit: www.gotcredit.com (Flickr)