We closed this position on August 18, 2021. A copy of the associated Position Update report is here.

Didi Chuxing (DIDI: $70-100 billion rumored valuation) is expected to go public sometime in July 2021. With a valuation rumored anywhere from $70 billion-$100 billion, the stock will earn our Unattractive rating.

We do not think investors should expect to make any money in Didi’s stock if the rumored valuation comes true.

A $100 billion valuation implies Didi will own 50% of the world ride share and food delivery market, a highly unlikely event given vast competition in an increasingly commoditized market.

We think the stock is worth no more than $34 billion, and Softbank needs the Didi IPO more than investors do.

Despite holding an estimated 90% of the ride sharing market in China, Didi’s business model is just as unprofitable as Uber (UBER) and Lyft (LYFT).

Uber and Lyft have shown investors that ride sharing is not a profitable business because of intense competition, low margins, and a lack of differentiation between services.

For Didi, Chinese regulatory risk looms large. Chinese regulators have recently broken up and issued record fines against other large Chinese firms. Reuters reports Didi is now under investigation for antitrust violations.

Our IPO research aims to provide investors with more reliable fundamental research.

No Profits Despite Revenue Growth and 90% Market Share

While ridesharing and food delivery apps fight for market share in the United States and Europe, Didi is the clear winner in the Chinese market. After merging with Kuaidi Dache in 2015 and acquiring Uber’s China business in 2016, Didi has an estimated 90% market share in China and generates 90% of its total revenues from its China Mobility segment, which consists of its ridesharing, taxis, chauffeurs, and hitch services.

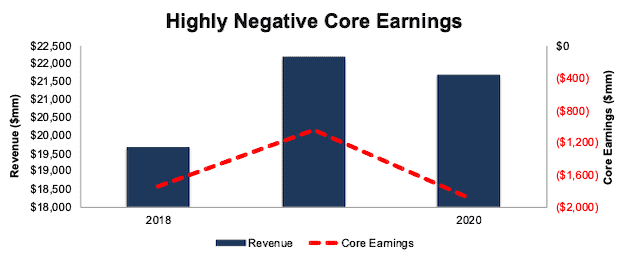

Nevertheless, like Uber and Lyft, Didi loses money. Losses accelerated in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revenue grew 5% compounded annually from 2018-2020 while Core Earnings[1] fell from -$1.7 billion in 2018 to -$1.9 billion in 2020. The company’s return on invested capital (ROIC) remains negative and has fallen from -12.4% in 2018 to -12.6% TTM.

Figure 1: Didi’s Revenue & Core Earnings: 2018-2020

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Unlike Uber and Lyft, which went public with double digit revenue growth rates, Didi’s revenue growth is much slower, which has some pointing out that its growth has plateaued. Shen Meng, director at a Beijing-based boutique investment bank notes, “Didi doesn’t have a solid foundation to support a valuation of $100 billion. The company’s growth has plateaued, while expanding overseas is no easy matter.”

Total Addressable Market Is Overstated

According to its F-1, Didi is “building the future of mobility.” Between ridesharing, food and grocery delivery, autonomous vehicle investments, and even shared bikes, Didi aims to serve all transportation needs. With a hand in many different markets, Didi broadly defines its total addressable market (TAM) as “mobility”, which, at $6.7 trillion, accounted for 8% of global GDP in 2020.

Such a vast TAM may interest new investors, given that Didi’s revenue in 2020 was $22 billion, or less than 1% of the firm’s estimated TAM. However, third-party estimates of ride sharing and food delivery, while still optimistic, estimate the market to be much smaller. For instance, in ridesharing:

- Markets and Markets projects the global ride-sharing market will be worth $185 billion in 2026.

- Mordor Intelligence projects the global ride-sharing market to be worth $210 billion in 2026.

In food delivery:

- Research and Markets expects the global online food delivery market to be worth $254 billion in 2028.

When we combine the Mordor Intelligence and Research and Markets estimates, Didi’s TAM in 2026 would equal roughly $416 billion,[2] which, is a fraction of the $6.7 trillion estimate in the firm’s F-1.

Same Broken Business Model: “No Economic Moat in Ride-Hailing”

Didi operates the same unprofitable business model as Uber and Lyft, which includes classifying drivers as contractors to keep labor costs down and charging below cost to entice users to the platform. We’ve long pointed out this model creates no lasting competitive advantage and can only last for as long as investors are willing to fund the losses. As Cui Dongshu, secretary general of the China Passenger Car Association, notes,

"There's no economic moat in the ride-hailing industry. The monopolistic advantage of Didi is the result of massive spending in subsidies during its early days.”

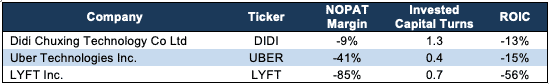

Figure 2 shows that Didi’s profitability, net operating profit after-tax (NOPAT) margin and ROIC, while above Uber and Lyft, remain negative. The company’s balance sheet efficiency (invested capital turns) is also superior to both peers, but it is not enough to offset low operational efficiency.

Figure 2: Didi’s Profitability Vs. Competition: TTM

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Business Model Is Not Evolving

While bulls claim that autonomous vehicles will ultimately eliminate driver costs, such a reality is years away at best. In the meantime, Didi will continue to offer services below cost and provide driver incentives to attract drivers to the platform, even at the detriment of profitability. From the F-1 (emphasis added):

“To remain competitive in certain markets and generate network scale and liquidity, we sometimes lower fares or service fees, offer significant driver incentives and offer other consumer discounts and promotions…. We cannot assure you that these practices would be successful in achieving their goals of attracting or maintaining the engagement of drivers and consumers, or that the positive impact of achieving those goals would outweigh the negative impact of these practices on our financial performance.”

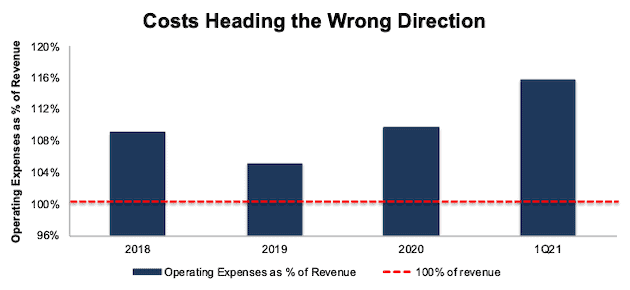

Figure 3 shows Didi’s operating costs as a percent of revenue and highlights how Didi’s strategy of attracting consumers and drivers is moving the firm further from profitability not closer.

Figure 3: Didi’s Operating Expenses as % of Revenue: 2018-2020

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Competition Outside China Could Further Increase Losses

Despite its inability to turn a profit with a near monopoly in the largest country in the world, Didi aims to expand internationally to drive growth. However, prospects for profitability outside of China look bleak, given increased competition and changing labor laws. Competitors around the globe include:

- Uber & Uber Eats – largely U.S. and Europe

- Just Eat Takeaway (acquired GrubHub) – U.S., Canada, Europe, & Australia

- DoorDash – U.S., Canada, and Australia

- Glovo – Europe & Africa

- Deliveroo – Europe, United Arab Emirates, and Australia

- Grab – Southeast Asia

- Bolt – Europe

- GoTo – Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines

- Cabify – South America

- Ola – India

- Zomato – India, UAE, and Lebanon

- Lyft – U.S. and Canada

- And many smaller operators, not to mention existing taxi services and delivery offered by restaurants (such as pizza)

Each of these services competes mainly on price, which drives negative profit margins.

China Regulatory Crackdown Already in Progress

Regulatory risk for companies operating under Chinese law should not be underestimated. Chinese regulators recently cracked down on some of the country’s largest internet companies, going as far as fining Alibaba $2.8 billion for alleged monopolistic conduct and providing “rectifications” for how it should do business.

Didi provides a specific section in its F-1, “Risks Relating to Doing Business in China” that outlines many ways in which the Chinese government can negatively impact its business and notes that its business may be subject to heightened regulatory scrutiny.

Reuters reported in June 2021 that the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) has begun an antitrust probe into Didi Chuxing, specifically looking at whether the firm used “competitive practices that squeezed out smaller rivals unfairly.” This investigation comes on the heels of reporting that in April 2021, Didi was among 30 companies ordered by the SAMR to conduct a self-inspection to identify and correct possible violations of anti-monopoly, anti-unfair competition, tax and other related laws and regulations. Then, in May 2021, The SAMR issued fines to 11 companies, including Didi, for violating anti-monopoly rules in merger & acquisition deals they made without seeking regulatory approval in advance.

Limited Stupid Money Acquisition Risk

Given its size, valuation, and regulations regarding foreign investment in Chinese firms, Didi is unlikely to be acquired, and instead, more likely to be the one acquiring as it expands internationally.

Investors hoping for a quick buyout should look elsewhere in the ridesharing/food delivery market.

Didi Is Priced to Take 50% of the Global Rideshare and Food Delivery Markets

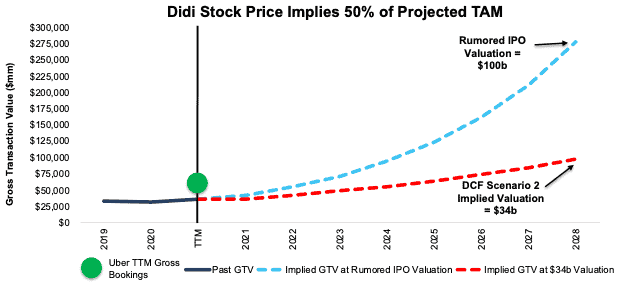

We use our reverse discounted cash flow (DCF) model to analyze and quantify the future cash flow expectations baked into Didi’s rumored valuation. Risk/reward at the rumored IPO valuation is unattractive.

To justify a $100 billion valuation, Didi must:

- Improve its NOPAT margin to 3% (compared to -9% TTM), which is similar to airlines prior to consolidation and

- grow revenue by 31% compounded annually for the next eight years, which is more than double the projected revenue CAGR of the global mobility market through 2025 (according to Didi’s F-1)

In this scenario, Didi would generate over $188 billion in revenue, or $50 billion in platform sales[3] in 2028, which is nearly 8x Didi’s TTM revenue. At its 1Q21 take rate (platform sales divided by gross transaction value [GTV]) of 17.8%, this scenario equates to nearly $278 billion in GTV[4] in 2028, or nearly 8x Didi’s TTM GTV and 4.5x Uber’s TTM gross bookings, a comparable metric to Didi’s GTV.

In other words, to justify a $100 billion valuation, Didi must capture 50% of its projected TAM[5] for rideshare and food delivery in 2028. For reference, Didi’s estimated market share in 2020 was roughly 17% of the TAM.

DCF Scenario 2: Growth Is More In-Line with Industry Expectations

We review an additional DCF scenario to highlight the downside risk should Didi’s revenue growth fall more in-line with industry expectations.

If we assume Didi:

- achieves a NOPAT margin of 5% (greater than airlines prior to consolidation) and

- grows revenue by 15% compounded annually for the next eight years (average of the projected global rideshare and food delivery market CAGR through 2026) then

DIDI is worth just $34 billion today/share today – a 66% downside to the rumored IPO valuation. See the math behind this reverse DCF scenario.

Figure 4 compares the firm’s implied future GTV in these two scenarios to its historical GTV, along with the GTV of Uber.

Figure 4: Rumored IPO Valuation Is Too High

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Each of the above scenarios also assumes Didi grows revenue, NOPAT, and FCF without increasing working capital or fixed assets. This assumption is highly unlikely but allows us to create best-case scenarios that demonstrate the expectations embedded in the current valuation. For reference, Didi’s invested capital increased $1.6 billion (8% of revenue) YoY in 2020. If we assume Didi’s invested capital increased at a similar rate in DCF scenario 2 above, the downside risk is even larger.

Red Flags Investors Need to Know About

With a lofty valuation that implies significant improvement in both revenue and profits, investors should be aware that Didi’s F-1 also includes these other red flags.

Public Shareholders Have No Rights: A downside of investing in Didi’s IPO, and other recent IPOs, is the fact that the shares provide little to no say over corporate governance. Investors in the IPO will get Class A Shares, with just one vote per share. Directors and early investors will hold class B shares. The exact number of votes per share have not been disclosed in Didi’s initial F-1, but the filing notes, “after this offering, the holder of Class B ordinary shares will have the ability to control matters requiring shareholders' approval.”

In other words, this IPO gives investors no voting power or control of corporate governance.

Who Really Benefits from This IPO: Given the unrealistic expectations implied by its valuation, it’s important to look at who really benefits from Didi going public at such an overvalued price. Beyond the co-founders, directors, and executives, the biggest winner in a Didi IPO is Softbank, with a 22% ownership stake in the company. Bloomberg reports Didi is the largest investment in SoftBank’s portfolio, which means the investment firm is heavily motivated to avoid another high-profile failure like the one we predicted for WeWork.

Interestingly, Uber stands to benefit from Didi’s IPO as well. As part of selling Uber China to Didi in 2016, Uber received a 13% ownership stake in Didi. With this IPO, Uber could see a windfall that further helps prop up its already overvalued business.

Non-GAAP EBITA Understates Losses: Long a favorite of unprofitable companies, Didi’s chosen non-GAAP metric, adjusted EBITA, a variation on the popular Adjusted EBITDA, shows a much rosier picture of the firm’s operations than GAAP net income or our Core Earnings. Adjusted EBITA gives management significant leeway in how it presents results.

For instance, Didi’s adjusted EBITA in 2020 removes $521 million (2% of revenue) in share-based compensation expense. After removing all items, Didi reports adjusted EBITA of -$1.3 billion in 2020. Meanwhile, economic earnings, the true cash flows of the business, are much lower at -$2.9 billion.

While Didi’s adjusted EBITA follows the same trend in economic earnings over the past three years, investors need to be aware that there is always a risk that adjusted EBITA could be used to manipulate earnings going forward.

We Don’t Know If We Can Expect Financial Transparency: Didi is going public as a foreign private issuer according to the rules under the Exchange Act. Accordingly, the company is exempt from certain rules and regulations that are applicable to U.S. domestic issuers. In its F-1, Didi notes “the information we are required to file with or furnish to the SEC will be less extensive and less timely compared to that required to be filed with the SEC by U.S. domestic issuers.”

More specifically, Didi is exempt from:

- the rules under the Exchange Act requiring the filing of quarterly reports on Form 10-Q or current reports on Form 8-K with the SEC

- the sections of the Exchange Act regulating the solicitation of proxies, consents, or authorizations in respect of a security registered under the Exchange Act

- the sections of the Exchange Act requiring insiders to file public reports of their stock ownership and trading activities and liability for insiders who profit from trades made in a short period of time

- the selective disclosure rules governing the release of material nonpublic information under Regulation FD; and

- certain audit committee independence requirements in Rule 10A-3 of the Exchange Act

Didi does plan to publish results on a quarterly basis as press releases but is not required to do so.

Making a lack of transparency even worse, Didi is incorporated in the Cayman Islands, which means the firm is permitted to adopt certain home country practices in relation to corporate governance matters that differ significantly from the NYSE & NASDAQ listing standards.

In other words, investors in Didi will have limited information on with to analyze the firm, and even when they do get material information, it will likely be less detailed and timely as one would expect from a U.S. firm.

Critical Details Found in Financial Filings by Our Robo-Analyst Technology

Fact: we provide superior fundamental data and earnings models – unrivaled in the world.

Proof: Core Earnings: New Data and Evidence, forthcoming in The Journal of Financial Economics.

Below are specifics on the adjustments we make based on Robo-Analyst findings in Didi’s F-1:

Income Statement: we made $1.2 billion of adjustments, with a net effect of removing $402 million in non-operating income (2% of revenue). You can see all the adjustments made to Didi’s income statement here.

Balance Sheet: we made $7.3 billion of adjustments to calculate invested capital with a net decrease of $2.4 billion. The most notable adjustment was $922 million in asset write-downs. This adjustment represented 5% of reported net assets. You can see all the adjustments made to Didi’s balance sheet here.

Valuation: we made $38.9 billion of adjustments with a net effect of decreasing shareholder value by $30.8 billion. The largest adjustment to shareholder value was $29 billion in preferred stock. This adjustment represents 29% of the rumored IPO valuation of $100 billion. See all adjustments to Didi’s valuation here.

Check out this week’s Danger Zone interview with Chuck Jaffe of Money Life.

This article originally published on June 21, 2021.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, Alex Sword, and Matt Shuler receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

[1] Only Core Earnings enable investors to overcome the flaws in legacy fundamental research, as proven in The Journal of Financial Economics.

[2] Assumes a global ridesharing TAM of $210 billion (equal to Mordor Intelligence estimate) and a global food delivery TAM of $206 billion in 2026. Global food delivery TAM assumes the market grows 11% compounded annually from 2021-2028 (equal to Research and Markets estimate), at which rate the market is worth $206 billion in 2026.

[3] Platform sales as a percent of revenue in 1Q21 was 26%. We calculate Didi’s 2028 platform sales as 26% of the $188 billion in implied revenue.

[4] Implied GTV is calculated as Platform Sales divided by Didi’s 1Q21 Take Rate. We assume Platform Sales, which are net of driver earnings and incentives, remain constant at 26% of revenue (equal to 1Q21) throughout the DCF scenario. Should Platform Sales increase as a percent of revenue (as they have in the past), the implied GTV would be even higher.

[5] 2028 TAM estimate equals Research and Market’s projected $254 billion global food delivery market in 2028 plus an estimated $298 billion global ridesharing market, for a TAM of $552 billion in 2028. The global ridesharing TAM assumes the global rideshare market continues growing at 19.2% annually from 2026 through 2028 (consistent with Mordor Intelligence’s estimated CAGR through 2026).