The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) passed ASU 2016-01, “Recognition and Measurement of Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities,” in January 2016 with implementation beginning in fiscal year 2018. This rule impacts the way companies account for changes in the fair value of securities on their income statement.

Most investors, if they’ve heard about this rule at all, will likely be familiar with it due to Warren Buffett’s criticism. In his 2017 letter to Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) shareholders, Buffett wrote:

“The new rule says that the net change in unrealized investment gains and losses in stocks we hold must be included in all net income figures we report to you. That requirement will produce some truly wild and capricious swings in our GAAP bottom-line… For analytical purposes, Berkshire’s ‘bottom-line’ will be useless.”

This new rule will have a significant impact on GAAP earnings for companies that hold large amounts of equity securities.

While the income statement impact of ASU 2016-01 is fairly easy to identify and reverse, the balance sheet impact is not. Fixing accumulated other comprehensive income (OCI), a key value in our calculation of invested capital, is much more complicated. Fortunately, our firm’s technology specializes in these kinds of complicated tasks[1].

This report analyzes the impact of ASU 2016-01 and explains how our models reverse the impact of this rule change to maintain comparability and accuracy of our cash flow and valuation models.

How the New Rule Works

Under the previous standard, companies had three options for how to classify and account for equity securities:

- Trading Securities: Changes in fair value were immediately recognized through net income.

- Available for Sale Securities: Changes in fair value were recognized in OCI and only reclassified into net income once the gains/losses were realized. Dividend income was immediately recognized through net income.

- Cost Method Securities: Asset was reported at cost minus any impairment losses. Only dividends or impairment losses were recognized in net income.

ASU 2016-01 eliminates these designations. All equity investments are now classified as equity investments or equity investments accounted for under the equity method.

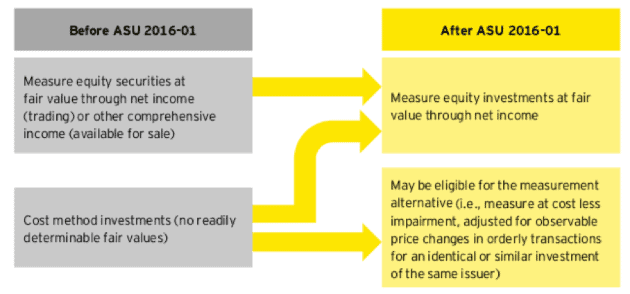

For investments that are not consolidated into a company’s financials or accounted for under the equity method, there are now only two options for companies. The can either recognize changes in fair value directly through net income, or they can use a method of accounting similar to the cost method described above. Figure 1, from EY, describes this change.

Figure 1: Accounting Treatment Before and After ASU 2016-01

Sources: EY

Effectively, most equity securities will now be treated the same way trading securities were prior to the rule change. Only securities for which there is no readily determinable fair value may be accounted for under a similar standard to the Cost Method. However, companies must adjust the fair value of when the transaction price for similar investments indicates a change in their values.

Impact on NOPAT

The impact of ASU 2016-01 on companies’ income statements is fairly easy to identify and reverse. In general, companies disclose unrealized gains and losses from equity securities in two ways:

- Non-Financial Companies: Unrealized gains and losses are included in “Other income (expense)” on the income statement.

- Financial Companies: Unrealized gains and losses are disclosed in the notes to consolidated financial statements

Non-financial companies that hold large amounts of equity securities – mostly tech giants such as Apple (AAPL), Alphabet (GOOGL), and Microsoft (MSFT) – include all gains and losses on those securities (both recognized and unrecognized) as part of “Other income (expense)”.

We have always excluded “Other income (expense)” from our calculation of net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) because it consists entirely of non-operating results. Therefore, we don’t have to make any changes to our data collection/treatment policy in order to account for this change to the income statement.

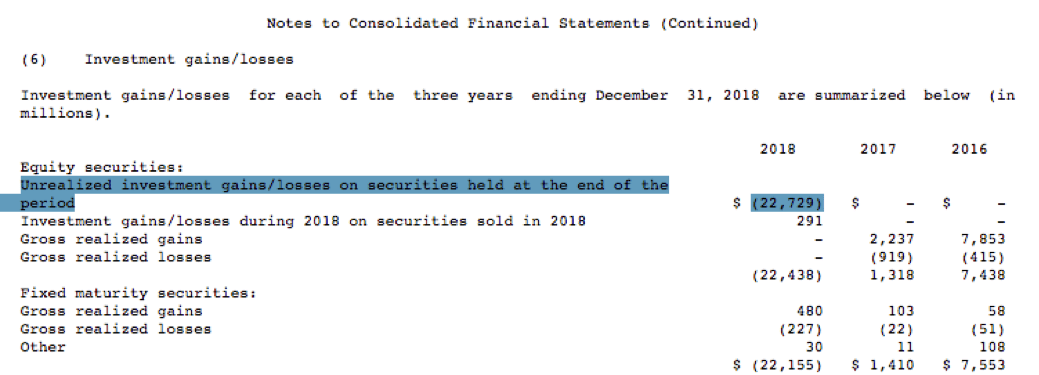

For financial companies, the disclosure is much less consistent. Berkshire Hathaway, for example, disclosed $22.2 billion in investment losses on the income statement in its 2018 10-K. On page 81, it disclosed that it had $22.7 billion in unrealized losses and $500 million in realized gains. Figure 2 has details.

Figure 2: Berkshire Hathaway Investment Gains/Losses in 2018

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Berkshire was forced to recognize $22.7 billion in losses (9% of revenue) on investments it plans to hold for the long term simply because the market was down in 2018. Investors that rely on GAAP net income would think that Berkshire’s profits declined from $44.9 billion in 2017 to $4 billion in 2018, a 90% decrease. Our adjustments, including an adjustment for unrealized losses, show that NOPAT actually increased by 15% over that same time.

Our Robo-Analyst[2] technology allows us to quickly identify and collect unrealized gains/losses from the financial footnotes to ensure our models are not distorted by this accounting rule change.

Impact on Invested Capital

Most of the analysis of ASU 2016-01 has focused on the fact that unrealized gains/losses are being reclassified into net income. But, as part of being reclassified into net income, they’re also being moved out of accumulated other comprehensive income (OCI). This change is a big problem, because accumulated OCI is one of the key adjustments we make to convert net assets to invested capital.

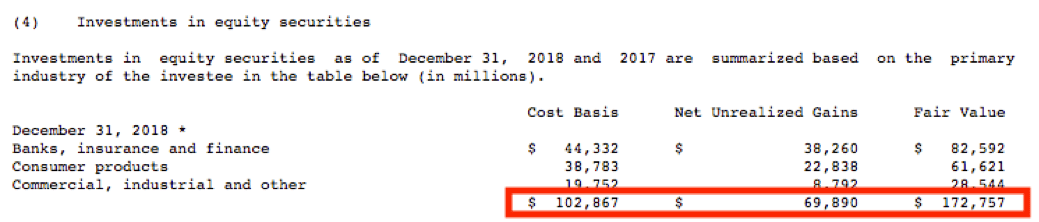

To understand the importance of accumulated OCI, it’s useful once again to look at Berkshire Hathaway. The company’s 2018 10-K discloses that it had $172.8 billion in equity securities on the balance sheet. However, Figure 3 (from page 79 of its 2018 10-K) discloses that its cost basis – the amount it actually paid for those securities – was just $102.9 billion.

Figure 3: Berkshire Hathaway Cost Basis vs. Fair Value of Equity Securities – 2018

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

In terms of understanding the invested capital of the business, the cost basis is clearly the number we should care about, as it’s the actual capital Berkshire invested, and upon which it must earn a return. However, the fair value is the number reported on the balance sheet.

Historically, it was easy to adjust the balance sheet figure to get back to the cost basis. We simply subtracted the accumulated OCI – which included net unrealized gains – from fixed assets.

With the adoption of ASU 2016-01, though, accumulated OCI no longer includes those unrealized gains. Fortunately, Berkshire clearly discloses the cost basis, fair value, and net unrealized gains of their equity securities each quarter, so we can manually recalculate accumulated OCI as it would have been under the old rule. We add back the cumulative net unrealized gains/losses to accumulated OCI (subtracting the amount that would be attributable to taxes and minority interests).

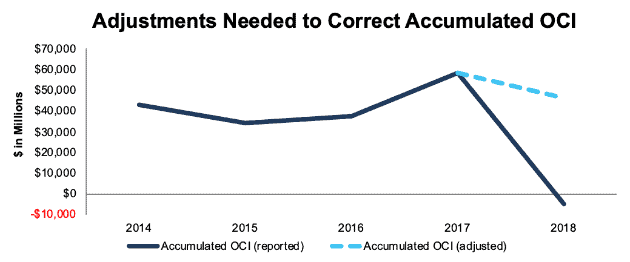

Figure 4 shows how applying this adjustment keeps Berkshire’s accumulated OCI more consistent with its historical average.

Figure 4: Berkshire Reported Vs. Adjusted Accumulated OCI: 2014-2018

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

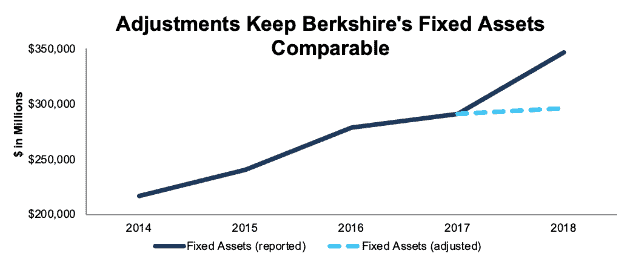

Figure 5 shows how correctly calculating OCI also allows us to provide a greater degree of comparability between Berkshire’s current and historical fixed assets.

Figure 5: Berkshire Reported Vs. Adjusted Fixed Assets: 2014-2018

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Companies That Don’t Disclose Net Unrealized Gains/Losses

Unfortunately, not all companies regularly disclose the cost basis, fair value, and accumulated unrealized gains/losses on their securities every quarter. For these companies, we have to collect and add incremental unrealized gains/losses in every reporting period to try to maintain comparability with historical accumulated OCI.

Every company has to disclose the amount of unrealized gains/losses reclassified out of accumulated OCI and into retained earnings upon adoption of the new standard, so we can apply the same treatment as we did for Berkshire at first.

After that point, we collect the incremental unrealized gains/losses in each reporting period. We add that value – net of estimated taxes, minority interests, and gains on sale of securities during the period – to the previously existing value for net unrealized gains/losses. Effectively, these numbers “stack” each quarter in order to maintain the comparability of accumulated OCI as best as we can.

This approach is suboptimal as it forces us to estimate the cost of taxes and minority interests in each reporting period. However, it is the best option we have for companies that don’t provide full disclosure of their cumulative unrealized gains/losses.

Impact on Financial Statements

Investors need to make these adjustments, both to the NOPAT and invested capital, in order to accurately understand the cash flows of companies impacted by the new rule and ensure the greatest degree of comparability with historical results.

Just accounting for the impact of ASU 2016-01 on the income statement is not enough. Investors tend to focus on the income statement, but understanding the balance sheet is just as important to measuring the cash flows of a business.

As Figures 4 and 5 showed, investors that don’t account for the new rule can significantly underestimate accumulated OCI, and therefore overestimate a company’s invested capital. In turn, overestimating a company’s invested capital will make its return on invested capital (ROIC) appear too low.

Since we know that ROIC is the primary driver of valuation, miscalculating ROIC will inherently give investors a misleading view of a company’s value. Accordingly, we adjust for the impact of ASU 2016-01, in addition to numerous other accounting rule changes and loopholes, to give investors the most rigorous calculation of ROIC possible.[3]

This article originally published on October 30, 2019.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

[1] For example, in “Core Earnings: New Data and Evidence,” Harvard Business School and MIT Sloan professors show that our unique footnotes adjustments enable investors to better predict future performance and generate alpha.

[2] Harvard Business School features our Robo-Analyst research automation technology in the case New Constructs: Disrupting Fundamental Analysis with Robo-Analysts.

[3] This paper compares our analytics on a mega cap company to other major providers. The Appendix details exactly how we stack up.