Editor’s Note: Accounting Standards Update 2016-02, which requires companies to record operating lease assets and liabilities on the balance sheet, went into effect for calendar year 2019. The adjustments/treatment of operating leases described below pertain to periods prior to 2019. For periods after 2019, we account for operating leases as explained here.

This report is one of a series on the adjustments we make to GAAP data so we can measure shareholder value accurately. This report focuses on an adjustment we make to our calculation of economic book value and our discounted cash flow model.

We’ve already broken down the adjustments we make to NOPAT and invested capital. Many of the adjustments in this third and final section deal with how adjustments to those two metrics affect how we calculate the present value of future cash flows. Some adjustments represent senior claims to equity holders that reduce shareholder value while others are assets that we expect to be accretive to shareholder value.

Adjusting GAAP data to measure shareholder value should be part of every investor’s diligence process. Performing detailed analysis of footnotes and the MD&A is part of fulfilling fiduciary responsibilities.

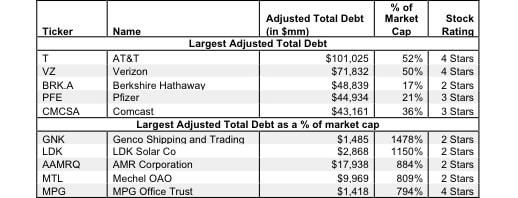

Adjusted total debt is the fair value of a company’s total short-term, long-term, and off-balance sheet debt. We use the fair value of a company’s total debt in our models because as it is a better representation of a company’s current and future obligations than the book value reported on the balance sheet. The fair value of a company’s total debt is the current amount the company would need to pay to retire the debt and settle the claims of the creditors. This fair value of debt is subtracted from shareholder value because the firm would need to settle these claims before it could return any cash to shareholders.

We have covered off-balance sheet debt before. Companies use off-balance sheet debt as a form of financing, which can disguise their true amount of debt to investors. (FASB recently announced a proposal to enact policy in line with how we treat operating leases: as capital leases on the balance sheet.)

2 replies to "Adjusted Total Debt – Valuation Adjustment"

Sorry for off-top… but i need your help!

Why do we take the current structure as the target structure when calculating the WACC, and any increase in debt will have no effect on the WACC? Yes, it is clear that when we raise debt for non-operating activities, the money just sits on the balance sheet …. but it is not very clear why this does not change the price of the company. So it turns out that if we borrowed debt over the long term, we don’t take it into account? Maybe at the moment we don’t have an optimal capital structure… I would be very grateful if you could explain this in detail on an intuitive level. I have not been able to find a clearer answer anywhere

Eugene,

You touched on several things in your question, but I will do my best to provide some more context around how debt is treated in our models, and specifically how it impacts WACC.

Our Adjusted Total Debt metric uses the fair value of debt, rather than the book value, and accounts for off balance sheet debt, so we believe this to be the best measure of debt that we can calculate. This is the number we will use when determining a company’s capital structure in any given period. As Adjusted Total Debt changes, WACC will also change, since the weighting of debt and equity capital changes.

It is true that a company’s target capital structure can be different from their current capital structure. They could have plans to borrow more or pay down debt. There are two main reasons that we don’t calculate a target capital structure or use one in our models.

1. This is not something that companies are required to disclose, therefore we often just don’t receive the necessary information to calculate this metric.

2. A company can always have a target capital structure, but the current capital structure is more reflective of reality when modelling debt or WACC.

The current capital structure is what we project forward when forecasting future periods in our DCF model. We know that the capital structure may change in the future, but for the purpose of forecasting, using the current capital structure is still the best assumption in our opinion. Trying to forecast changes in capital structure introduces a lot of unneeded volatility.

To summarize:

1. Yes, changes in debt do impact WACC

2. We do not attempt to calculate a target capital structure

3. The current capital structure is the best assumption when forecasting future periods.

Also, clients with access to our valuation models are able to use overrides to change WACC as they desire.

Let us know if you have any other questions.