Check out this week’s Danger Zone interview with Chuck Jaffe of Money Life.

One of the biggest risks to a short thesis is what we call “stupid money risk.” This phrase refers to the risk that an already highly overvalued firm gets acquired at the current, or even higher, valuation, thereby wiping out all shorts. Recent examples of stupid money acquisitions include Microsoft (MSFT) buying LinkedIn for $26 billion and Salesforce (CRM) buying Demandware for $2.9 billion.

Now, we have the surge in stupid money acquisition risk rising for Tesla (TSLA), as Elon Musk publicly announced he wants to take the firm private. In light of this ongoing saga, we examine possible motives as well as how stupid money acquisitions can hurt acquirers even more than the short sellers. For example, just last week, Steinhoff International and Newell Brands (NWL) saw misguided acquisitions come back to bite them.

Tesla Going Private Screams Stupid Money Acquisition

Musk’s buy out idea is a publicity stunt. Musk aims to distract from the company’s ongoing production woes and cash burn by portraying it as under siege by short-sellers and the media (a tactic reminiscent of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos). A war with short-sellers could be easier to win than the battle against the existing auto giants. As Jim Chanos put it in an interview on CNBC:

“The short position is the best thing the stock has going for it. ‘Musk vs The Shorts’ is a far better narrative than ‘Tesla vs Mercedes/Audi/Porsche.’”

The fact that Musk can even play the “take Tesla private card” is a stark reminder of the limitations of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). Academics who accept market efficiency as dogma ignore the role that noise traders[1] can play in distorting prices from their fundamental value. Musk is a reminder that noise traders can also be CEO’s making buyout offers based on ego or misaligned incentives. As we’ll show below, when executives act as noise traders, shareholders of the acquiring firms tend to suffer far, far worse than the short-sellers.

Steinhoff’s Stupid Money Acquisition Hurts Shareholders 10x More than Short Sellers

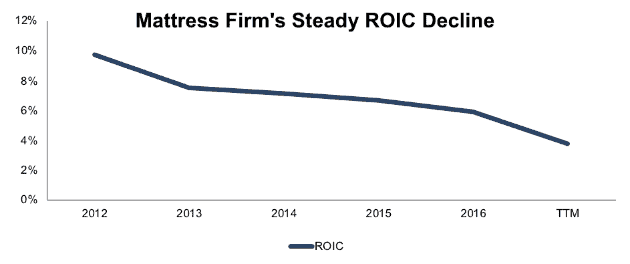

Figure 1 shows the decline in the return on invested capital (ROIC) of Mattress Firm in the years leading up to its acquisition by South African retail giant Steinhoff International. From 2012 to the trailing twelve-month period prior to acquisition, Mattress Firm’s ROIC declined from 10% to 4%.

Figure 1: Mattress Firm’s ROIC from 2012 to Acquisition

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

Despite its declining ROIC, Mattress Firm continued to invest in the business and -$1.6 billion in free cash flow from 2013-2016. In light of such underwhelming performance, it’s hard to imagine what value a potential acquirer could see, but Steinhoff decided to acquire the company at $64/share, more than double the stock price from a few months earlier when we called Mattress Firm dangerously overvalued and put it in the Danger Zone.

Steinhoff didn’t appear to care too much about Mattress Firm’s fundamentals, as it spent just five days on due diligence and didn’t even acknowledge the company’s $1.4 billion (58% of market cap) in off-balance sheet debt.

As the business continues to decline, Mattress Firm is now reportedly considering bankruptcy in order to get out of its leases and close underperforming stores. The company’s woes were easy to spot back in 2016, but Steinhoff’s managers did not appear to consider doing proper due diligence a priority.

When we put Mattress Firm in the Danger Zone a few months before the acquisition, there were 7.2 million shares sold short. When the stock price increased from ~$31/share to the acquisition price of $64, those shorts lost ~$240 million. Meanwhile, Steinhoff paid $2.4 billion for a company that may not have any equity value remaining, meaning its loss could be up to 10x worse than the short sellers’.

Newell’s Stupid Money Acquisition Hurts Shareholders 100x More than Short Sellers

Bill Ackman’s appearance at the 2015 Sohn Conference is best remembered for his long thesis on a pharmaceuticals company called Valeant (VRX) that was growing rapidly through acquisitions and covering up its losses with shady non-GAAP accounting. We all remember how that turned out.

Fewer people remember that Ackman also pitched another company that followed a similar strategy. Consumer products company Jarden, another Ackman holding at the time, was also spending big on acquisitions while seeing its ROIC and cash flows steadily decline.

Fortunately for Ackman, Jarden got bailed out by another company following the same strategy in Newell Rubbermaid (NWL). Our analysis of the deal showed that Newell should only have paid about half of the $23 billion it spent on Jarden, and we eventually put the combined company in our Focus List – Short Model Portfolio.

The Jarden acquisition has been a significant loser for NWL shareholders, who have seen their share price decline by 60% over the past year. The company now seems to be recognizing the failure of the deal and is selling off many of the pieces acquired in the Jarden acquisition.

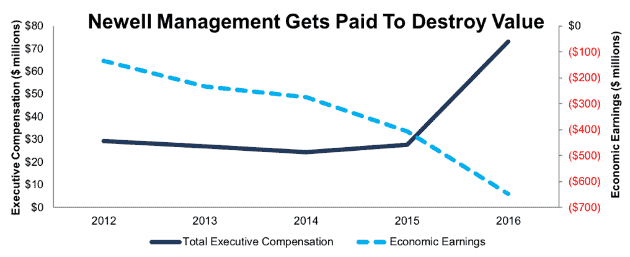

However, Figure 2 shows that the acquisition worked out well for Newell’s executives, who saw their compensation nearly triple in 2016 after the deal was completed.

Figure 2: Compensation for Top Newell Executives: 2012-2016

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

CEO Michael Polk’s compensation grew from $14 million in 2015 to $22 million in 2016, while president Mark Tarchetti’s pay tripled from $6 million to $18 million.

The jump in pay came from the acquisition putting the company in a larger peer group and helping executives hit their sales growth and adjusted EBITDA metrics. By tying executive compensation to metrics that don’t consider capital allocation, Newell failed to align their interests with shareholders and incentivized them to overpay for Jarden.

When we put Jarden in the Danger Zone, there were 10.9 million shares sold short. When the stock price increased from $47/share to $60/share, those short sellers lost ~$140 million. On the other hand, when the Jarden acquisition was completed on April 15, 2016, Newell had a market cap of $21.3 billion. Since then, it has lost $11.7 billion in market value, more than half its value. NWL investors lost ~100x as much as short sellers.

Both the Newell/Jarden and Steinhoff/Mattress Firm deals were easy to identify as overpriced at the time, by both ourselves and others. However, in both cases managers’ incentives were not aligned with shareholders. These management teams acted as self-interested noise traders, overpaying in their respective acquisitions to benefit themselves at the expense of shareholders.

As a result, short sellers that attempted to profit from the overvaluation of Jarden and Mattress Firm took big losses, but investors in Newell and Steinhoff that ignored those short sellers’ warnings lost anywhere from 10x to 100x more. Meanwhile, short sellers could recoup their losses by continuing to short the stocks of these acquirers.

Back to Tesla

What do a consumer goods manufacturer and a South African retailer have to do with Tesla, you might ask? Simple: both companies illustrate the dangerous feedback loop that can occur when both traders and executives make decisions based on noise rather than fundamentals.

In the case of Newell and Jarden, Bill Ackman acted as a noise trader, buying into Jarden’s acquisition-driven growth while ignoring its declining profitability. His pitch attracted a host of self-directed investors that bought into the story and propped up the price to the point that Newell’s executives, motivated by their own misaligned incentives, bought in.

Elon Musk and a large portion of Tesla’s shareholders are engaged in a similar feedback loop. Musk’s outlandish promises and insults to analysts drive away institutional investors and attract self-directed traders that buy into his cult of personality. These traders don’t appear to care about the fundamentals anyway, so Musk spends even less time worrying about cash flows and more time sharing memes that make fun of short-sellers.

This feedback loop is how we get an offer to take Tesla private at $420/share, a valuation that implies the company will immediately achieve pre-tax margins of 10% – slightly better than Toyota (TM) – and grow revenue by 29% compounded annually for 10 years, at which point it would earn more revenue than GM did in 2017 with margins that are 200 basis points higher). See the math behind this dynamic DCF scenario.

A valuation of $420/share implies that the market is confident that Tesla can simultaneously achieve superior margins than the most profitable major automaker in the world and sell more vehicles than the largest automaker in North America. These expectations are so disconnected from the fundamentals of Tesla’s business (burning $8bn in cash over the last 3 year and struggling to manufacture 5,000 Model 3’s in a week while GM sells over 180 thousand vehicles in a week) that the idea of anyone paying $420/share is absurd.

The bottom line is that most die-hard Tesla bulls don’t care about fundamentals, and the stock’s surge has forced many asset managers to get on board rather than risk missing out on its run and underperforming their benchmark. Noise traders, not fundamentals, are in control of Tesla’s stock price. Being a noise trader can be profitable in the short term, but it usually ends badly in the long term.

As the Tesla noise gets more ridiculous, even the noise traders might get cold feet about the stock’s dangerously high valuation. Tesla is one of several stocks we see in a “Micro-Bubble” that could burst soon.

Overall markets remain mostly efficient, but that efficiency can come at great costs to sophisticated investors. Noise traders make it harder for fundamental investors to justify the cost of performing proper due diligence on securities. What’s the point of spending all the time poring through 10-Ks and 10-Qs to understand a company’s cash flows if noise traders are just going to ignore the cash flows anyway?

Our goal is to help markets be more efficient by reducing the cost of this information arbitrage by using Robo-Analyst technology[2] to reduce the amount of time it takes to accurately assess a company’s cash flows. We want to provide more accurate measures of fundamental corporate performance[3] and better transparency into the cash flow expectations implied by stock prices to help companies and fundamental investors allocate capital more intelligently. By making diligent fundamental analysis easier and more accessible, we aim to reduce the impact of noise traders and increase the efficiency of the capital markets.

This article originally published on August 15, 2018.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

[1] Shiller, Robert J., et al. “Stock Prices and Social Dynamics.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, vol. 1984, no. 2, 1984, pp. 457–510. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2534436.

[2] Harvard Business School features the powerful impact of our research automation technology in the case New Constructs: Disrupting Fundamental Analysis with Robo-Analysts.

[3] Ernst & Young’s recent white paper “Getting ROIC Right” proves the superiority of our ROIC calculation.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.

Photo Credit: Intellectual (Pixabay)