How ASU 2016-01 Impacts Invested Capital and OCI

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) passed ASU 2016-01, “Recognition and Measurement of Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities,” in January 2016 with implementation beginning in fiscal year 2018. This rule impacts the way companies account for changes in the fair value of securities on their income statement.

Most investors, if they’ve heard about this rule at all, will likely be familiar with it due to Warren Buffett’s criticism. In his 2017 letter to Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) shareholders, Buffett wrote:

“The new rule says that the net change in unrealized investment gains and losses in stocks we hold must be included in all net income figures we report to you. That requirement will produce some truly wild and capricious swings in our GAAP bottom-line… For analytical purposes, Berkshire’s ‘bottom-line’ will be useless.”

This new rule will have a significant impact on GAAP earnings for companies that hold large amounts of equity securities.

While the income statement impact of ASU 2016-01 is fairly easy to identify and reverse, the balance sheet impact is not. Fixing accumulated other comprehensive income (OCI), a key value in our calculation of invested capital, is much more complicated. Fortunately, our firm’s technology specializes in these kinds of complicated tasks[1].

This report analyzes the impact of ASU 2016-01 and explains how our models reverse the impact of this rule change to maintain comparability and accuracy of our cash flow and valuation models.

How the New Rule Works

Under the previous standard, companies had three options for how to classify and account for equity securities:

- Trading Securities: Changes in fair value were immediately recognized through net income.

- Available for Sale Securities: Changes in fair value were recognized in OCI and only reclassified into net income once the gains/losses were realized. Dividend income was immediately recognized through net income.

- Cost Method Securities: Asset was reported at cost minus any impairment losses. Only dividends or impairment losses were recognized in net income.

ASU 2016-01 eliminates these designations. All equity investments are now classified as equity investments or equity investments accounted for under the equity method.

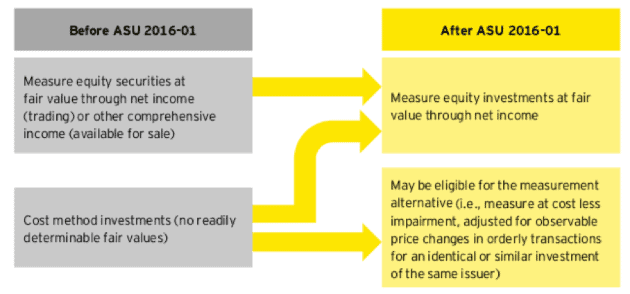

For investments that are not consolidated into a company’s financials or accounted for under the equity method, there are now only two options for companies. The can either recognize changes in fair value directly through net income, or they can use a method of accounting similar to the cost method described above. Figure 1, from EY, describes this change.

Figure 1: Accounting Treatment Before and After ASU 2016-01

Sources: EY

Effectively, most equity securities will now be treated the same way trading securities were prior to the rule change. Only securities for which there is no readily determinable fair value may be accounted for under a similar standard to the Cost Method. However, companies must adjust the fair value of when the transaction price for similar investments indicates a change in their values.

Impact on NOPAT

The impact of ASU 2016-01 on companies’ income statements is fairly easy to identify and reverse. In general, companies disclose unrealized gains and losses from equity securities in two ways:

- Non-Financial Companies: Unrealized gains and losses are included in “Other income (expense)” on the income statement.

- Financial Companies: Unrealized gains and losses are disclosed in the notes to consolidated financial statements

Non-financial companies that hold large amounts of equity securities – mostly tech giants such as Apple (AAPL), Alphabet (GOOGL), and Microsoft (MSFT) – include all gains and losses on those securities (both recognized and unrecognized) as part of “Other income (expense)”.